The evolution of education from ancient caves to AI classrooms prompts reflection on past, present, and future implications. | Photo: iStock/Getty images

The story of education is the story of humanity itself – one that evolved from the flickering firelight of ancient caves to the glowing screens of AI-powered classrooms. It’s imperative that we reflect on how we arrived here and the way we have reimagined how knowledge is created, shared, and internalised over the years.

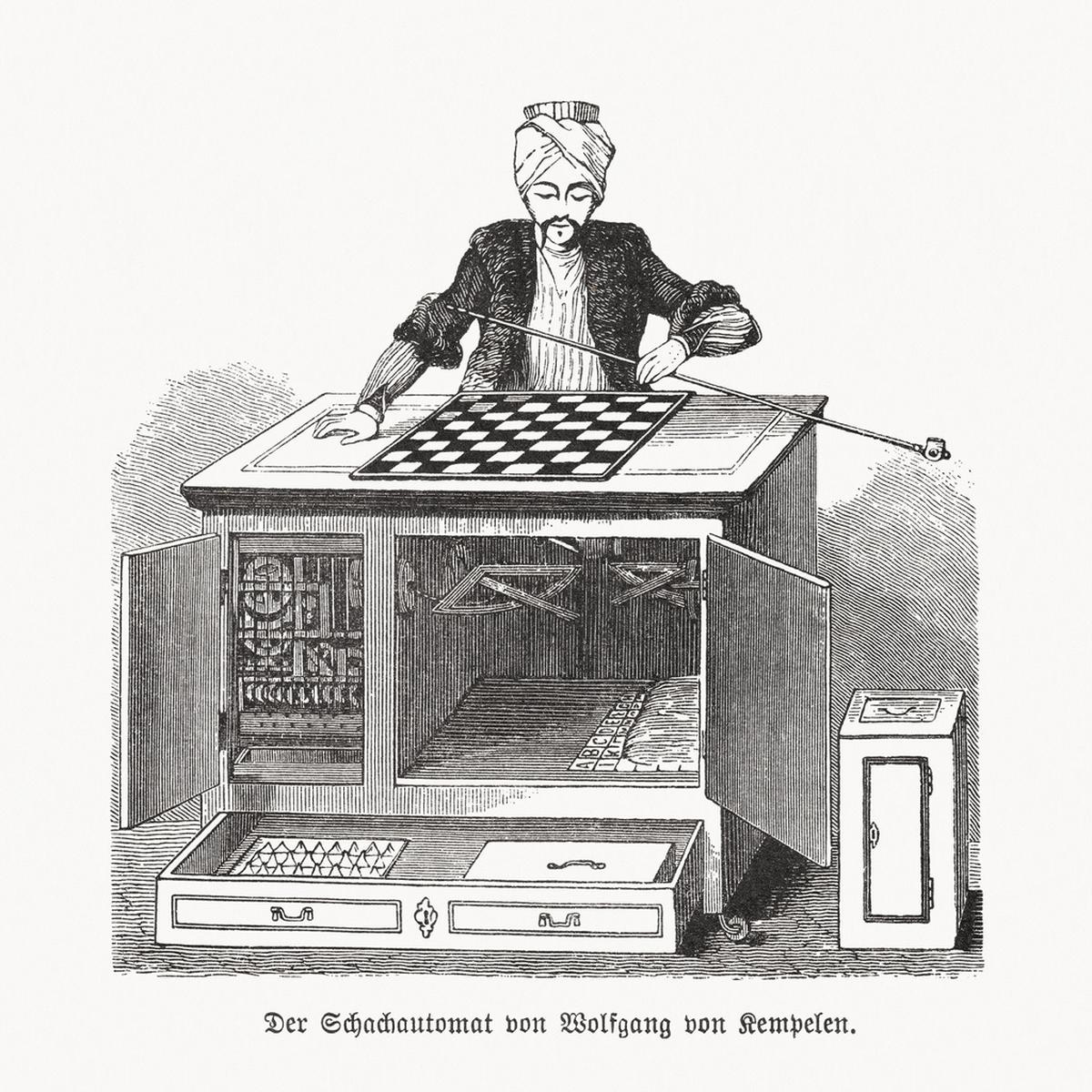

Kempelen’s Mechanical Turk

In 1770s a Hungarian bureaucrat called Wolfgang von Kempelen presented a show with an automaton that he had built. An automaton is a machine that operates on its own without the need for human control. Automatons were all the rage during the 18th century; inventors like Jacques de Vaucanson, Pierre Jaquet-Droz, and Henri Maillardet amazed the public with brilliant human-like contraptions capable of doing such things as playing an instrument or writing.

Kempelen’s automaton topped them all, anyway — or at least appeared to. It was a wooden figure in oriental attire, seated behind a great cabinet with a chessboard on top of it. Kempelen would start his performances by opening the doors of the cabinet to reveal to the audience the clockwork machinery within. When the doors were shut, he would wind the machine using a key.

A spectator would approach and sit opposite the automaton to play a game of Chess. The automaton would then come to life, picking up the pieces and making moves. To add further surprise to that, the human opponent would soon realise that the automaton was a formidable opponent; it would win the majority of the games it played.

Automaton chess player, called “The Turk” by Hungarian author and inventor, Wolfgang von Kempelen. | Photo: iStock/Getty images

Starting in the 1780s Kempelen’s automaton, also referred to as the Turk or the Mechanical Turk, was placed on tour throughout Europe. It played against several prominent human players. It was played by Benjamin Franklin in Paris. The Chessmaster François-André Philidor was able to defeat it but stated that the game had been a difficult one. When Kempelen passed away in 1804, the automaton was purchased by an engineer, Johann Maelzel, who went on to travel with it and perform.

It was not until Karl Gottlieb von Windisch’s reveal in his “Inanimate Reason” essay published in 1784 that the truth was revealed – There was a chess player hidden within the cabinet, following the game on a tiny chessboard and moving the Turk using levers.

As much as it was a farce, the Turk inspired Charles Babbage, an English mathematician, to invent the world’s first automatic mechanical calculator and digital computer in 1822. In less than a couple of centuries, a chess-playing computer called Deep Blue defeated a human world champion in a chess match in 1997.

Early years of building interest in AI

Kempelen’s Mechanical Turk has had an outsized impact not only in the field of entertainment but in the general idea of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and its role in many areas including education. Today, AI’s growing presence in education can be traced back to that early fascination with machines that could seemingly think for themselves.

This early spectacle was part of building interest in AI and its subsequent inclusion in learning environments. It questioned the potential of machines in replicating human capabilities, signalled the possibility of human-machine interaction, and forced us to think critically about the best way in which technology could serve the process of learning.

Human’s educational journey began not in classrooms but in the forest in 50,000-3000 BCE with direct transmission of survival knowledge from elders to youth through demonstration, stories and supervised practice. It evolved into traditional education in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China (3000-500 BCE) centred on literacy and vocation. The period of 500 BCE-500 CE was perhaps a pivotal one as Socrates introduced the dialectic approach to learning- one which encouraged critical thinking rather than memorization and focused on citizenship with an all-round holistic education.

The medieval period saw a shift towards religious schools maintaining knowledge before leading the world to the Renaissance and Enlightenment (1400-1800 CE) period that witnessed a transition to secular education, driven by the invention of the printing press and thinkers such as Locke and Rousseau. It wasn’t until the nineteenth century that education systems became universal, based on the Prussian system and on Horace Mann’s faith that education could level the playing field.

The twentieth century saw developments from John Dewey and Maria Montessori in child-led experiential learning. Technology pervaded the schooling system in the later part of the twentieth century with products such as PLATO, clearing the way for distance learning. Between 2000-2020, education was transformed by the internet and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), a pace further fuelled by the Covid-19 pandemic. The current period, with AI’s advent, represents a fundamental shift in educational possibilities, bringing both unprecedented opportunities and complex challenges across the teaching and learning process.

Published – March 06, 2025 08:03 pm IST