Last week, the Central Bureau of Investigation filed a closure report stating that actor Sushant Singh Rajput died by suicide. The news was widely reported, but there were no breathless discussions on the agency’s finding.

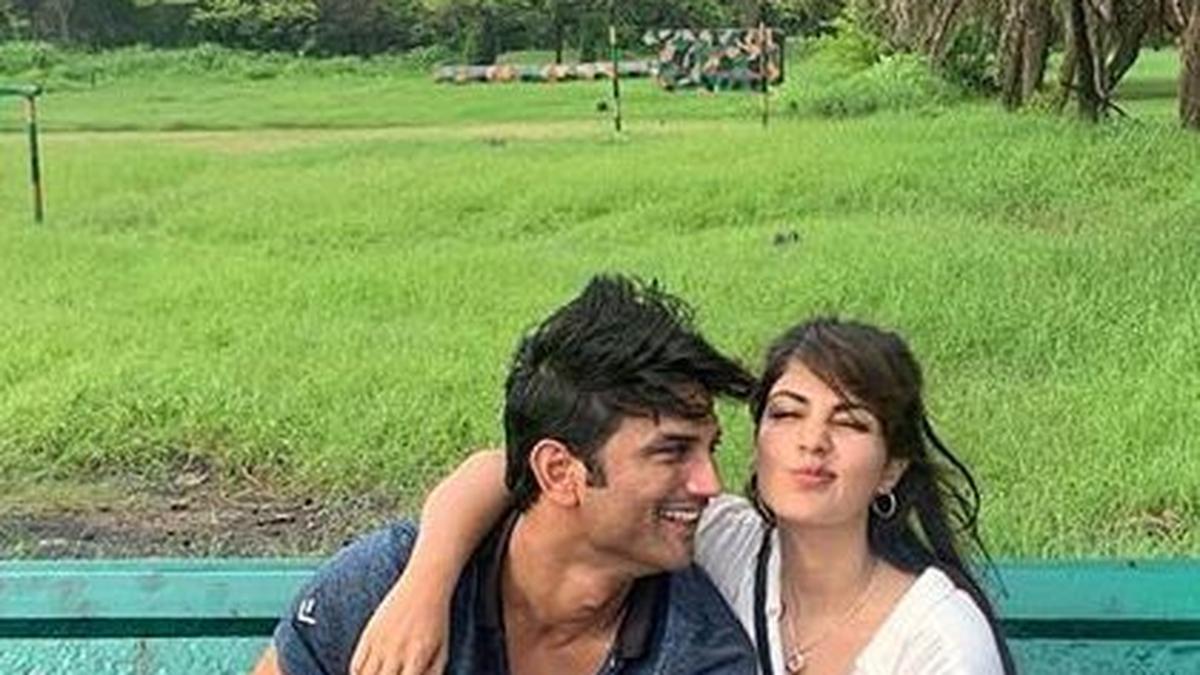

This was a far cry from June 2020, when the Bollywood actor was found dead in his apartment. Rajput’s girlfriend, Rhea Chakraborty, herself an actor, suddenly found herself in the midst of a firestorm, especially after his father lodged a complaint against her, accusing her of taking his son’s money and abetting his death. The Narcotics Control Bureau arrested Chakraborty on charges of supplying drugs to Rajput. News channels relentlessly vilified her. In an interview, the actor recalled that she was called “chudail (witch), kaala jaadu karne waali (one who performs black magic), and naagin (snake).”

The Blame-Woman Syndrome, characterised by putting the responsibility of anything that goes wrong on a woman, is all too common. As German historian Ingrid Sharp wrote in a paper, ‘Blaming the Women: Women’s ‘Responsibility’ for the First World War’, “…In Germany during and after the First World War,… women were blamed in various quarters for first failing to prevent the war and then to bring it to an end.” In an article in The New Humanitarian in 2007 on how HIV/AIDS often has more devastating consequences for Mozambican women than it does for men, Maria Cecilia de Mendonça Pedro, a sociologist, said, “When children are born with genetic problems, the mother is blamed… When the couple lacks children, the woman is blamed and the husband has the right to return her to her parents…” Whenever sexual assault cases are reported in India, someone unfailingly comes along to ask why the woman chose to step out or wear the clothes she did.

The tendency is puzzling. Women have always been regarded as the “weaker sex”. Is it not paradoxical then that the Blame-Woman Syndrome is rooted in the belief that women wield enormous power to change the course of lives and histories?

The tendency also originates from certain gendered stereotypes, which are not just pervasive, but institutionalised, as this editorial points out. During elections, for instance, despite the enormous strides that women have made in politics, slogans continue to have sexist undertones. Women, according to the unwritten but widely cited Constitution of Patriarchy, are money-grubbers, cunning, and provocative.

Women are now more financially independent and less likely to take things sitting down. This has led to uncertainty about long-established gendered roles. As an article in the Washington Post pointed out 30 years ago, “Blaming the woman offers quick relief to a society that is anxious about its future.” Fighting back tirelessly against the blame, like Chakraborty did, is the only way for women, too, to get relief and emerge vindicated.

Toolkit

In his novel, Deviants, Shantanu Bhattacharya captures how attitudes towards homosexuality have changed in India over the last half-century through his exploration of the lives of three gay men who are part of the same family. In an interview with The Hindu, Bhattacharya said: “I’m from a queer generation that couldn’t wait to grow up, that avoids reminiscing, and felt like it didn’t fit into groups — our stories are being told in retrospect.”

Wordsworth

Gender-neutral language: According to the European Parliament, this is a general term “covering the use of non-sexist language, inclusive language, or gender fair language.” Examples include the use of the word ‘chairperson’ instead of ‘chairman’, or ‘police officer’ instead of ‘policeman’ or ‘policewoman’. Last week, the Chhattisgarh government made a significant amendment to the Adoption Act, 1908, replacing the term ‘adopted son’ with ‘adopted child’ in all legal documents. The State Finance Minister said this would ensure gender neutrality.

Somewhere someone said something stupid

“Is this all we found at France télé? It’s shameful. She has a horse’s face.”

Cyril Hanouna, French TV host, on Laury Thilleman, former Miss France

Women we met

Meera Sitaraman

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Meera Sitaraman has been working with Theatre Nisha in Chennai for over 15 years as an actor, designer, playwright, stage manager, and director. She is also one of the few women in the technical side of theatre, which involves, for instance, carrying heavy lights and fixing them. “I was initiated into the craft of lighting during a Prakriti Foundation workshop in 2012. Initially, it was a struggle to establish myself in the field since people would be like, ‘Oh, a girl is doing the lighting?’ But over time, since I have established myself, it’s become easier,” she says. Why is lighting mostly done by men, I ask. “One of the reasons is because lighting is done at night, so it’s not always conducive for women,” says Sitaraman.

Published – March 30, 2025 08:41 am IST