Branching away from the bustle of London’s Oxford Street, one encounters the Oriental Club at Stratford House, an institution that once served as a gathering place for the men of the East India Company. It remains a silent custodian of their colonial legacy, its walls imbued with the weight of history. Charles Dickens once remarked upon its membership, describing it as “composed of noblemen, MPs, and gentlemen of the first distinction and character”.

Within its grand halls, relics of the empire abound — a ram’s head snuffbox, the detritus of a world defined by conquest, and portraits of popular names who served in the subcontinent. Arthur Wellesley surveys the room with unrelenting resolve. Nearby hangs the likeness of Stringer Lawrence, the architect of British victory over the French at Tiruchi (Trichinopoly) during the Second Carnatic War. William Nott, whose iron will secured Kabul for the British, finds his place among them, alongside Mountstuart Elphinstone, Governor of Bombay, and Eyre Coote, who made his name during the Battle of Vandavasi (Wandiwash). Presiding over them all are two figures whose very names evoke the memory of empire’s ascent — David Ochterlony and Robert Clive. The latter, in particular, needs no introduction.

Among those who once frequented the Oriental Club was Dr Wynne Peyton, a man whose life, like so many of his contemporaries, was bound irrevocably to the East. An Irishman of formidable intellect and ambition, Peyton served in the Indian Medical Service under Governor-General Francis Hastings during the Third Anglo-Maratha War, a conflict that established British dominance over the subcontinent. .

The Chess Valley, where Peyton’s mansion Goldingtons is

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Following his service, Peyton settled in Madras, a city where the tides of empire ebbed and flowed ceaselessly. In 1809, he married Eliza Robertson in the cantonment town of Bellary. To them, two daughters were born — Mary, born in March 1810, and a second child who died the same day she was born in 1811. Nine days later, at the tender age of 21, Eliza herself succumbed, leaving her grieving husband to bury her in the hallowed grounds of St Mary’s Co-Cathedral on Armenian Street. For Peyton, it marked the beginning of a new chapter.

A desire to grant her a British education while he pursued his career in Madras, led him to send his surviving daughter Mary, to England aboard the Lady Castlereagh (a ship launched in 1803) when she was four years old. Peyton himself ascended the ranks of his profession with distinction, eventually attaining the prestigious position of president of the Medical Board of Madras, a role that cemented his legacy in the annals of colonial administration.

By 1826, however, the pull of home had grown too strong. In July of that year, he embarked on his journey westward, boarding the General Palmer — a vessel that, decades later, would be immortalised in infamy when a brutal murder occurred aboard, the victim’s body concealed within a barrel while the murderer absconded to New Zealand. Peyton disembarked in Britain and soon made a fateful decision. He purchased a vast 1,000-acre estate in Carrick-on-Shannon, reclaiming his ancestral ties to Ireland after a lifetime in the service of an empire that had drawn him far from its shores.

Yet, his years in India had forever altered him, and he found himself drawn once more to the orbits of those who shared in his experience.

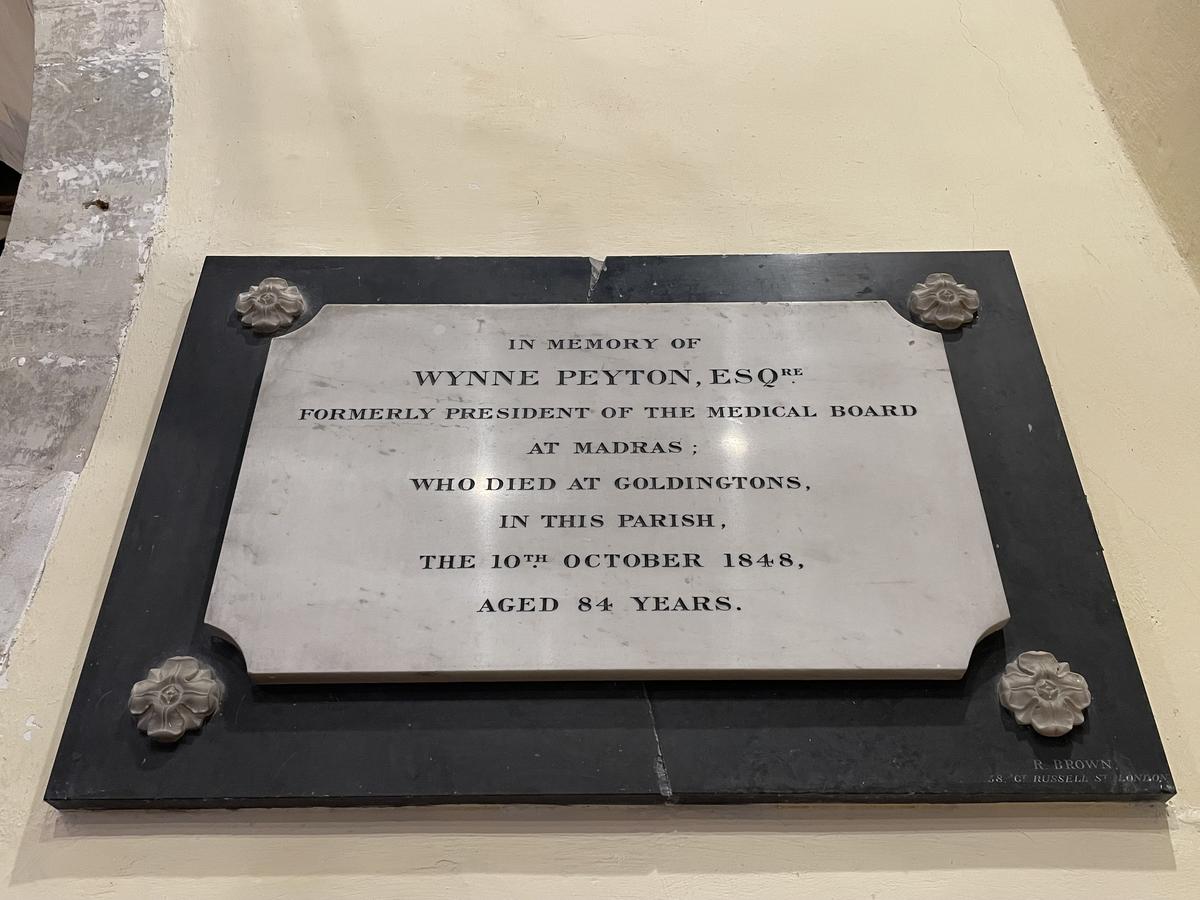

Wynne Peyton’s plaque

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

London remained a siren call, and he frequently travelled the 25 miles to where the Oriental Club provided him a space for reminiscence. Here, he was in the company of kindred spirits — men who had once ruled distant lands and who, like him, now sought solace in shared memories. Among them were the likes of William Bentinck, Edward Clive (son of Robert Clive), and Alexander Burnes, the ill-fated diplomat whose role in the Great Game against Russia ended in a brutal assassination in Kabul in 1841. There, too, was Hudson Lowe, Napoleon’s relentless jailer in Saint Helena, and Governor-General Charles Metcalfe, a man steeped in the politics of empire. He would have conversed with the great industrialist Dwarkanath Tagore and the Parsi philanthropist Jamsetjee Jeejebhoy, whose fortunes were made upon the trade routes of the East.

Peyton was in the presence of power, rubbing shoulders with General Archdale Wilson who captured Delhi and Lucknow during the tumult of 1857, and James Hogg, chairman of the East India Company and father of Stuart Saunders Hogg, who played a pivotal role in Calcutta’s administration. The corridors of the club echoed with the voices of commanders and potentates — Neville Chamberlain, who once led the Madras Army, and the exiled Maharaja Duleep Singh, son of the great Ranjit Singh, whose very inheritance had been wrested from him. Standing beside the young prince was his guardian, John Login, the man responsible for delivering the legendary Kohinoor diamond into the hands of Lord Dalhousie, forever altering its destiny.

On October 10, 1848, after a life spent in the service of empire, Dr Wynne Peyton breathed his last. He had lived to the remarkable age of 84, his years spanning the zenith of British dominion in India. In death, as in life, he found himself entwined with history, his mortal remains interred in the 12th-Century Church of the Holy Cross in Hertfordshire. There, beneath the ancient stone where he rests, is a man whose journey had carried him from the battlefields of India to the quiet embrace of the English countryside, his name now but a whisper among the annals of Madras.

Published – April 07, 2025 04:44 pm IST