One winter, many years ago, I was gifted a ticket to witness the Republic Day parade: the kind of gift you cannot refuse without offending the giver, and the kind of giver you cannot afford to offend. I grudgingly took myself to the venue, bereft of all distractions other than a novel clutched under my arm, a shield against the hours of tedium to follow.

At the entrance I was stopped, and informed that my book could proceed no further. I protested, held the pages up to the light, and pleaded that in no way was this creased paperback a security threat – to no avail. The book was confiscated, and I proceeded empty-handed to witness the celebration of the Republic. Once I was safely out of the security guard’s earshot, I muttered, “at least enjoy the novel. It’s all about military idiocy.”

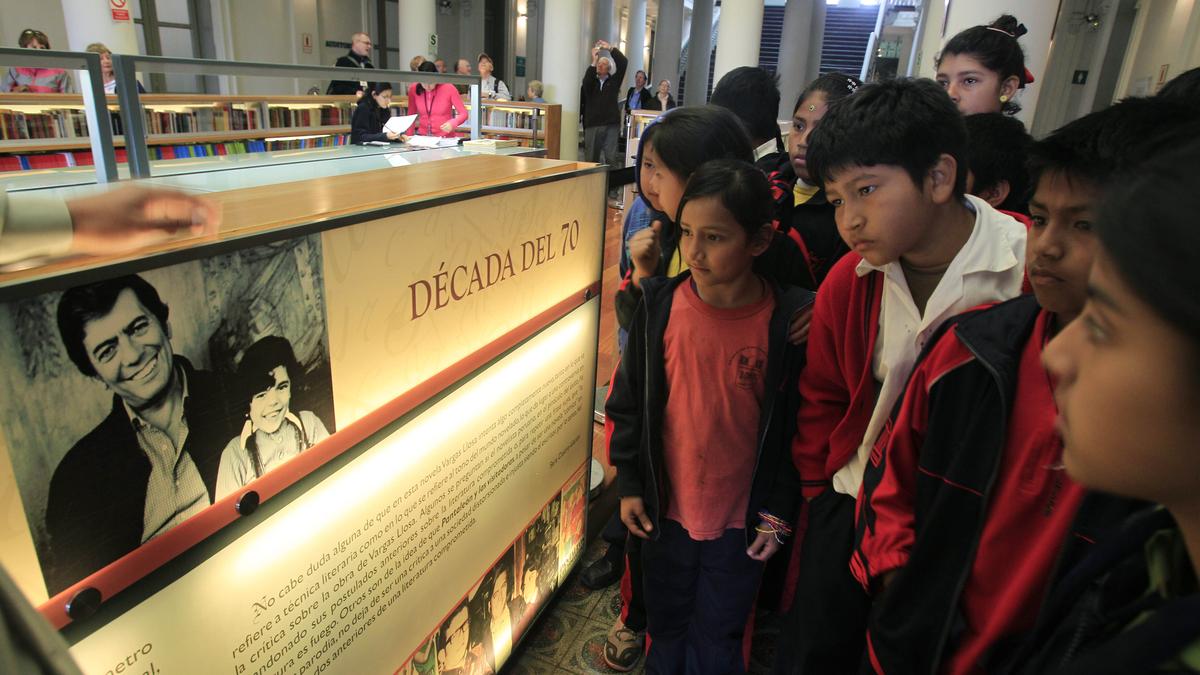

The book was The Time of the Hero, the 1963 debut novel of the Peruvian writer, Mario Vargas Llosa — who would no doubt have smiled to hear of this anecdote. Vargas Llosa passed away on April 13, leaving behind a storied and controversial legacy as writer, essayist, and politician.

One of the foremost writers of what is popularly known as the “Latin American boom,” Vargas Llosa began his career sharing the anti-authoritarian, left-wing instincts of many of his contemporaries, such as Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Julio Cortazar. Unlike them, however, he ended his career (and his life) as a partisan of right-wing politics, a supporter of Jair Bolsonaro and Javier Milei, a votary of Friedrich Hayek, and a frequently conservative commentator in the pages of Spain’s largest newspaper, El Pais. In the middle of all this, there was also a failed presidential run in the Peruvian election of 1990 — something that Latin American writers and poets are no strangers to.

One person, many views

What are we to make of this? Vargas Llosa himself would perhaps see no contradiction: after all, in his epigraph to The Dream of the Celt, he quoted Jose Enrique Rodo: “each one of us is not one, but many. And these successive personalities that emerge one from the other tend to present the strangest, most astonishing contrasts among themselves.” From Fidel Castro to Jair Bolsonaro: an astonishing contrast indeed: as if the writer himself was a collection of disquieting heteronyms out of a Fernando Pessoa novel!

Yet even as his political commitments pitched and tossed like a boat in a lightning storm, there remained a deeper consistency to his literary work. Consider, by way of example, The War at the End of the World (1981), The Feast of the Goat (2000), and The Dream of the Celt (2010). Separated by three decades and dealing, respectively, with a millenarian civil war in 1890s Brazil, the last day in the life of Dominican Republic dictator Rafael Trujillo, and the tempestuous life of the Irish revolutionary and anti-slavery advocate, Roger Casement, each of these novels illuminate a theme that is woven into the warp and weft of Vargas Llosa’s writing: a revulsion towards power, and a will to unveil the violence that is masked underneath the exercise of power in our world; in the words of Marx, “bar[ing] the head of the monster by knocking off the crown which shielded and concealed it.”

Disdain for power

At his best, this disdain of power was mirrored by an empathy towards those who struggled against it.

This shines through most vividly in his decision to novelise the life of Roger Casement in The Dream of the Celt. Casement — the “fallen archangel” — was one of history’s patron saints of lost causes: an anti-colonial radical in the era of Empire, a queer man in the age of the trial of Oscar Wilde, and an Irish revolutionary in the doomed Easter Rising. In excavating his life, Vargas Llosa became something akin to what Stuart Jeffries writes about Walter Benjamin: “… a historian… not just of defeated humans but of expendable things that, back in the day, had been the last word.” And, like Benjamin, a salvager of the detritus, the shipwrecks of history.

And yet, although he is perhaps best known for his so-called “political works” — especially the Latin American tradition of anti-dictator (or “caudillo”) novels — Vargas Llosa was anything but a one-dimensional writer. Consider another trilogy of novels, separated by time and space: Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter (1977), The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto (1997), and Bad Girl (2006). The first, a picaresque story of a radio jockey in 1950s Lima falling in love with a woman twice his age; the second, a novel of sexual fantasies mediated by the paintings of Egon Schiele; and the third, a modern-day retelling of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, which pulls us around the world.

And if the theme of the previous trilogy is power, then the currency of this is its opposite and mirror image: transgression. These stories are Vargas Llosa at play, ludic excursions into realms that we would otherwise only tiptoe around.

If Mark Twain once wrote that “against the assault of laughter, nothing can stand,” then it is the puckish, transgressive whimsy of these novels that is perhaps the greatest threat to the kind of power that Vargas Llosa despised so much: because if there is one thing that power insists upon, it is that it be taken seriously; and if there is one thing that these novels do, it is to laugh that conceit to scorn.

‘Impulse of sympathy’

And so I think back once more to my dog-eared copy of The Time of the Hero, and wonder where it finally ended up.

We can always do with a searing critique of military culture in our modern-day, hyper-militarised societies; but perhaps, after reading the book, the man who confiscated it went on a Vargas Llosa journey, and found Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter, The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto, and Bad Girl.

Perhaps they drew laughter, and the understanding that — along with Zbigniew Herbert, another great sceptic of power — it is better to “trust … the pure impulse of sympathy” rather than the “feeble imagination” of power that only knows how to take itself too seriously.

If so, then in the great beyond, Mario Vargas Llosa — who once said that he wrote because he was unhappy — might feel content.

Gautam Bhatia is a writer, reviewer, and most recently, the author of ‘The Sentence’ (Westland 2024).

Published – April 18, 2025 08:30 am IST