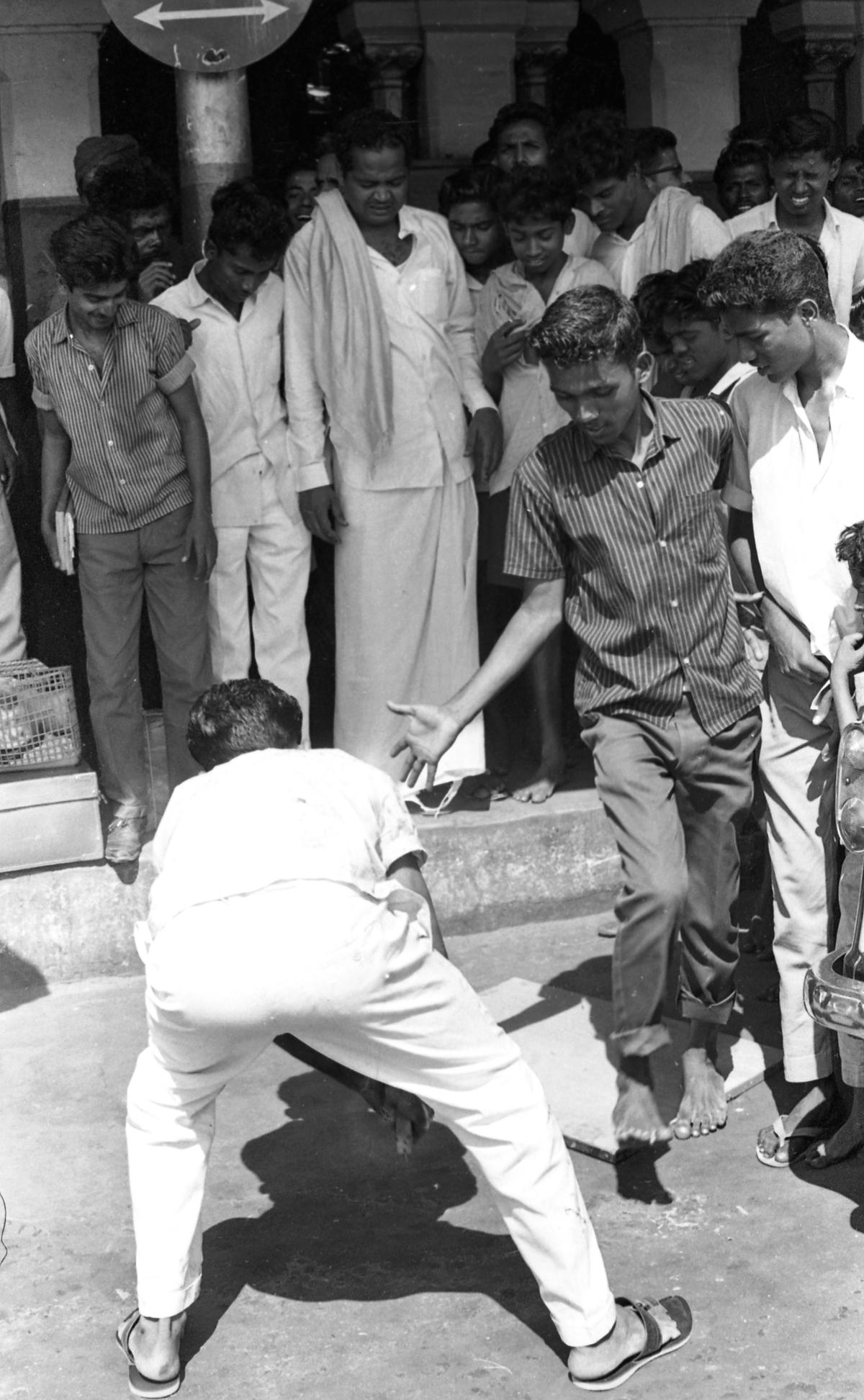

Spontaneous agitation: College students being detained for staging a protest against the imposition of Hindi in Madras in 1967. The widespread protests forced the DMK government to announce closure of educational institutions in the State and adopt a resolution in the Assembly on January 26, 1968, against the three-language formula.

| Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

A political controversy is raging in Tamil Nadu over the BJP-led Union government’s insistence on adoption of the three language formula proposed in the National Education Policy-2020. Against this backdrop, it would be worthwhile to see how the two language policy of teaching only Tamil and English in schools came into force in 1968.

In early 1968, Parliament adopted The Official Languages (Amendment) Act, 1967, to permit the continuation of English, in addition to Hindi, as the language of official communication, deferring an earlier policy of adopting Hindi as the sole official language in the country. It also adopted the Official Language Resolution, 1968. This resolution provided for taking steps to implement the three-language formula fully in all States: the study of a modern Indian language, preferably one of the southern languages, apart from Hindi and English in the Hindi-speaking areas, and of Hindi along with the regional languages and English in the non-Hindi-speaking areas.

Anti-Hindi agitation by college students in Madras in 1967, students burn effigy.

| Photo Credit:

THE HINDU ARCHIVES

This triggered widespread protests by students in Madras that forced the first DMK government, headed by C.N. Annadurai, to announce closure of educational institutions. It was then that the Madras government adopted a resolution in the Assembly on January 26, 1968, rejecting the three-language formula.

Domination by one region

The resolution argued that the adoption of one of the regional languages as the Official Language of India, in a land of different languages, cultures, and civilizations, would result in the domination by one region over the other regions. It proposed that until Tamil and other national languages were adopted as official languages, English should continue as the official language and the Constitution should be suitably amended.

“Whereas this House is of the opinion that the Official Languages (Amendment) Act, 1967, passed by Parliament, does not serve to achieve the above objective, but will result in creating, among those connected with the administration, two divisions with mutual hatred, friction, and inevitable confusion, this House resolves to continuously strive to realise the objective as stated above. As the Resolution on the Language Policy passed along with the Official Languages (Amendment) Act will result in injustice to the people in the non-Hindi regions by placing them at a disadvantage with new burdens, and as all the political parties are unanimously of the opinion that the said resolution should not be enforced, this House resolves that the Union Government should immediately suspend the operation of that resolution and devise ways and means to ensure that the people in the non-Hindi regions are not subject to any disadvantage or additional burden,” the resolution said.

Anti-Hindi agitation by college students in Madras in 1967, students burn effigy.

PHOTO: THE HINDU ARCHIVES

| Photo Credit:

STAFF

“This House is of the opinion that the said resolution, by insisting on the enforcement of the three-language formula, aims to force Hindi on the people of non-Hindi regions with the ultimate object of making only Hindi the sole Official Language,” it added.

The House then resolved that “the three-language formula shall be scrapped, and Tamil and English alone should be taught, and Hindi should be completely eliminated from the curriculum in all schools in Tamil Nadu”.

The then Deputy Prime Minister, Morarji Desai, felt that the two-language formula adopted in the Madras Assembly was not in the interests of the country. “…the Union Government was considering measures to deal with the situation. This thing could not be discussed in public,” he said, according to a PTI report published in The Hindu on February 6, 1968. However, much earlier, Annadurai had rejected the charge that the government motion “indirectly revived the DMK’s secession move”, which it had abandoned some years ago. “On the other hand, he said, it was the Centre’s language policy and scheme that paved the way for this. He pointed out that if he had aimed at separation, the best thing would have been for him to leave the language issue alone. He had not done that; he was making earnest attempts to solve the language problem and tackle the situation created after the passage of the Official Languages Act,” said a report in The Hindu dated January 24, 1968.

Anti-Hindi agitation by college students in Madras in 1967 being taken in a police van.

| Photo Credit:

THE HINDU ARCHIVES

Speaking in the Assembly on January 23, Annadurai told critics, who pleaded that national unity should be placed above the language question, that he too was repeating the same request. “If national unity was the need of the hour, why did the Congress rake up the language issue now, in spite of the advice of eminent leaders like Mr. C. Rajagopalachari against it,” he asked. The Chief Minister pointed out that in Canada, the French and English people lived together harmoniously for over 100 years, without forcing the issue of a link language. On some members suggesting that people should give up their claims and make sacrifices for the sake of national unity, he countered, “But, are we the only people who should always give up our claims and make sacrifices? What is the sacrifice the Hindi-speaking people have made to preserve national unity? What is the suffering they have undergone to achieve this?”

‘A bogey created by the Congress’

He also felt that the plea for a link language among the people of the various States was itself a bogey created by the Congress. He said that in a vast country like India, there could be no single language linking the people. A few days later, at a symposium on the national language organised by students of Tenali in the present day Telangana, Annadurai said the people did not ask for an official language. “The whole problem was created by the Indian Government,” he felt. “I sincerely believe in and stand for the sovereignty of India. I am not for secession, but I also want every one of us to live as equals and not as masters and servants,” he said.

Published – February 18, 2025 10:04 pm IST