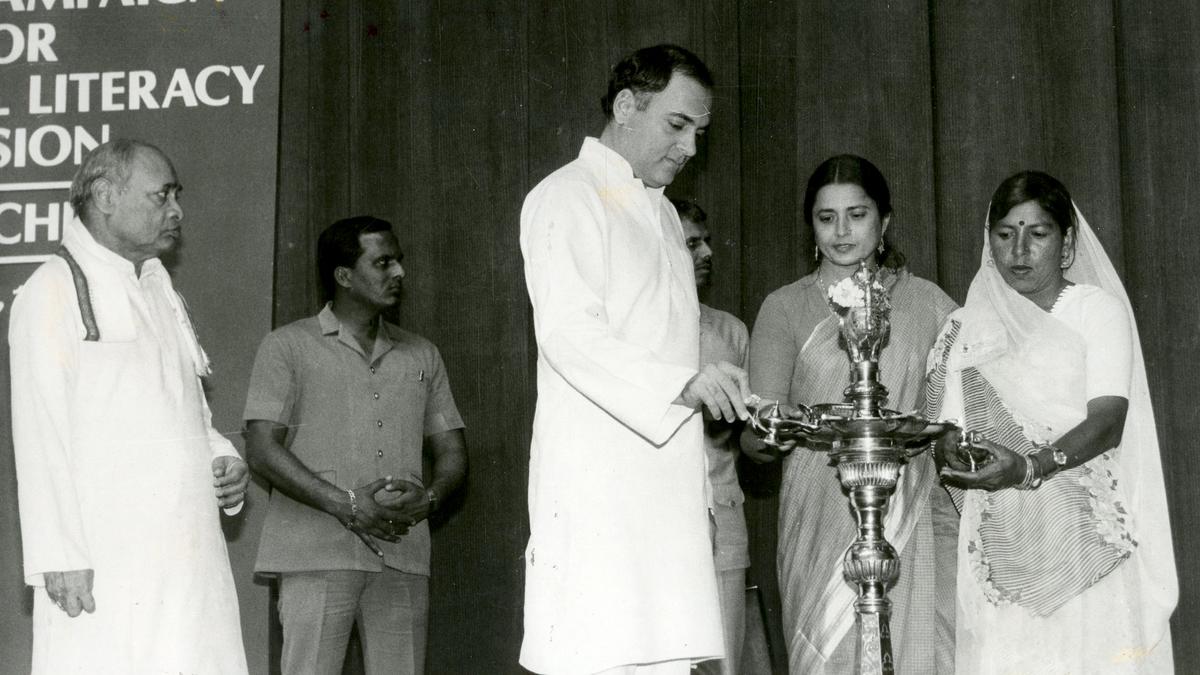

PM’s word: Speaking in the Lok Sabha on May 8, 1986, Human Resource Development Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao (left) reiterated Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s assurance that Navodaya schools would not be imposed on any State. Here, Rajiv Gandhi is launching the mass campaign for the National Literacy Mission in New Delhi on May 5, 1988.

| Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

The three-language formula under the PM Schools for Rising India (PM SHRI) scheme that sets out to establish more than 14,500 exemplar schools has triggered a row between the Centre and the Tamil Nadu government. A similar squabble broke out in the mid-1980s when the Centre introduced the Navodaya concept of schools. In January 1985, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi announced the formulation of the National Policy on Education (NPE). The NPE was formally unveiled in May 1986, but the controversy erupted in June 1985 following reports that the Centre wanted to open a school in Ramanathapuram district.

Tamil Nadu vs Centre: The PM Shri controversy explained | Focus Tamil Nadu

‘Hindi being favoured’

Education Minister C. Aranganayagam of the AIADMK, responding to the three-day debate in the Legislative Council on the demands for grants for his department, criticised the Centre’s move to establish “schools of excellence” (Navodaya schools) in every district as model schools. The Minister, who begun his career as a school-teacher, asked, “What else can the intention be other than imposing Hindi,” according to a report in The Hindu on June 13, 1985. Aranganayagam had argued that the three-language formula, prescribed by the Centre and some of the States, favoured Hindi and went against regional languages.

On May 8, 1986, when the Lok Sabha discussed the merits and demerits of the draft policy, Minister for Human Resource Development P.V. Narasimha Rao, who became the Prime Minister in June 1991, surprised his critics by saying he welcomed the controversy. At the same time, he reiterated the Prime Minister’s assurance that such schools would not be imposed on any State. On the contentious issue of medium of instruction, he said that in the first two years, the instruction would be in the local language and then the schools would switch over to the three-language formula.

In the meantime, the AIADMK government, despite having friendly equations with the Congress government at the Centre, continued to voice its opposition. In April 1986, Chief Minister M.G. Ramachandran came out against Hindi medium at Navodaya schools and made this stand known to the rest of the country through his address (read out by Electricity Minister Panruti S. Ramachandran) at the National Development Council meeting in New Delhi.

A twist in 1986

The Navodaya episode had its own share of twists and turns. When the AIADMK government was badly in need of the Union government’s support to have the Legislative Council abolished (for which steps were being taken then), there was a change in the tone of the Education Minister. In mid-May 1986, he referred to the Prime Minister’s assurance that Hindi would not be imposed through the Navodaya schools. “What is wrong if we get ₹2 crore for model schools for talented students so long as the Centre agrees not to impose Hindi,” Aranganayagam asked. The change came about on May 18, four days after the Assembly adopted a resolution by 136 to 25 votes, recommending to Parliament the Council’s abolition. The Congress, an ally of the ruling AIADMK, had stayed away from the voting. Later, the Union Human Resource Development Ministry issued a statement that the medium of instruction in Navodaya Vidyalayas would be the mother tongue or the regional language up to Class VII or VIII and thereafter, it would be Hindi or English, this newspaper reported on May 19, 1986.

As the announcement led to strong protests, former Union Minister C. Subramaniam, who was also Madras Education Minister in the 1950s, batted for the inclusion of regional languages as the medium of instruction. “In the field of education, adjustments to suit local conditions are inevitable, and no uncompromising stand need be taken,” he said, calling for the enforcement of the three-language formula in “letter and spirit” even in Hindi-speaking States. It would not be in the interest of Tamil Nadu to forego the benefits of substantial investment that the Centre proposed to make to build schools with free boarding and lodging and modern facilities, especially in rural areas, he said in a statement on June 19, 1986, urging the State to take “a realistic view and follow an imaginative policy”.

Karunanidhi rejects plea

However, the AIADMK government stood firm. Since then, this has been the State’s position, regardless of the party in power. About 15 years ago, a few Congress MLAs made an open appeal to Chief Minister M. Karunanidhi to allow the establishment of Navodaya schools, but he did not budge. The Union Ministry’s annual report says 661 Navodaya schools have so far been sanctioned in 27 States and eight Union Territories, except in Tamil Nadu “which has not yet accepted the Navodaya Vidyalaya Scheme”. Of them, 650 are functional. As on November 30, 2023, there were about 2.88 lakh students, of whom Other Backward Classes accounted for around 38%, Scheduled Castes 24%, Scheduled Tribes 20%, and the general category 18%. The rural-urban ratio was 89:11. While the pass percentage of students at Class X and XII was of the order of 97% to 99% from 2021 to 2023, at least 85% of them got the first division. What was more important was the high strike rate of the Navodaya students clearing the National Eligibility-cum-Entrance Test in 2023 with 76%. In the case of the Joint Entrance Exam (Advanced), it was around 32%. Perhaps, C. Subramaniam’s wise words — “a realistic view and an imaginative policy” — are relevant for all those involved in the current controversy over the three-language formula.

Published – February 25, 2025 11:07 pm IST