‘Letters are love. They may mean nothing to the world but they can mean the world to us.’

| Photo Credit: Getty Images

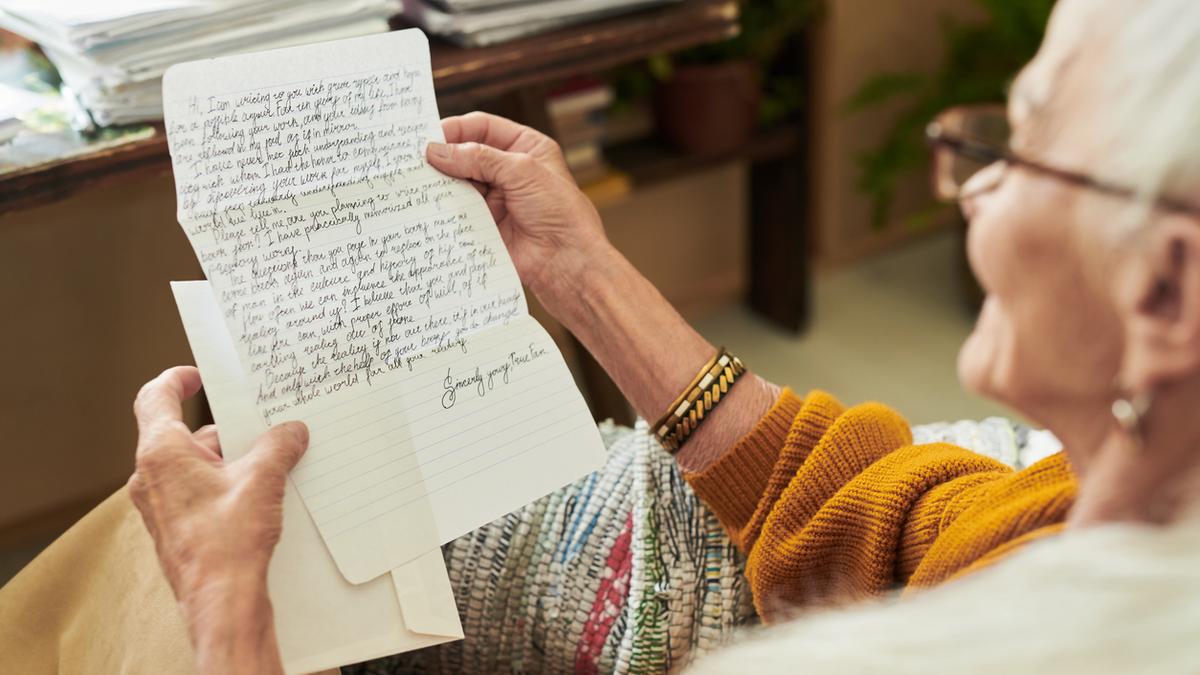

The other day, my partner Bishan showed me a letter his mother had found.

It was addressed to him, from his father, written in Bengali, just a few sentences long, each sentence in an ink of different colour. Bishan must have been a little boy at the time and didn’t remember getting it. There was nothing of great importance in it. Just a father writing to say he would be home soon and promising to bring colour pencils. Long before our emoji-studded WhatsApp messages, he had filled the letter with little sketches — a drawing of the train that would bring him home, a smiley face to say he was well, and flowers.

Bishan’s father had passed away in March. The funeral rituals were done, the ashes immersed, even the one-month memorial was over. But that long-lost handwritten note made my heart ache. It was a reminder of loss. But of love as well. They are, it turns out, two sides of the same sheet of paper.

Portrait from an unsent letter

Five years after my own father died, my niece discovered a letter he had written us, tucked away in the files on his desk. My father had been a man of few words, loving but quiet. Adulthood had left us with even less to say to each other. My mother was the letter-writer in the family, filling every square inch of an aerogramme with mundane details of life back home. She usually left a sliver of space for my father to fill in with his spindly ant-like script. “How are you? Take care of yourself. We are well.” He wrote, I suspect, under her orders.

But in those unsent letters my niece discovered, my father spoke in a way we never had as adults. He talked about the world. “I have very little sense of God. I just think what was meant to happen happens. Perhaps it was time for man to go to the moon.” He told us not to mourn him with rituals. He hoped we would lead good lives, not just ones that fed our self-interest. “If it can help others it will fill your heart as well. But if you help others, don’t be tempted to think of yourself as superior to them.”

Those letters made me rue the conversations we never had. My father lived through Independence. Absorbed in my own life it had never occurred to me to ask him what he did on that day. But in reading those letters, I could hear his voice.

Between the lines

Nowadays, we get almost no letters. The courier only brings bulletins, bills and parcels. Letters moved to email. And then to WhatsApp and Telegram. We instant message now. Will another generation one day stumble upon WhatsApp messages and feel the same pang? Perhaps. It’s foolish to sentimentalise paper just because we can touch it. When I went to America, I had no WhatsApp. I wish I did. I would wait avidly to hear the rattle of the mailbox and rush down hoping to see the blue corner of an aerogramme letter from India amidst the bills and catalogues. The news in it would be a month-old but it was the handwriting that mattered. I could imagine my family sitting down and writing them. I could see my father’s desk, my mother’s bed. Years later as I prepared to leave America, I found boxes and boxes of letters. I didn’t know what to do with them.

This was not Nehru writing to Indira Gandhi from prison or Martin Luther King Jr. writing from Birmingham Jail or Albert Einstein writing to his daughter about “a powerful force that, so far, science has not found a formal explanation for”. That force is love. Letters too are love. They may mean nothing to the world but they can mean the world to us.

Perhaps that is why we save letters. They are a record. They serve as reassurance that we mattered. When a friend died in his 20s, I went back to his letters, filled with raunchy accounts of his escapades in Delhi barsatis. His grieving sisters asked if I would share some of them with him. It was a side of their brother they had not really known.

Now we live in a world where we communicate more than ever across time zones and borders. But most of us live in a world without letters. Even WhatsApp messages can be set to disappear after a while. Email runs out of storage. But a letter is different.

I was wrong when I said that little letter from Bishan’s father said nothing of importance. It did. It said someone cared about you enough to sit down and write you a little note and draw pictures of flowers and railway trains.

How can that ever be of no importance?

The writer is the author of ‘Don’t Let Him Know’, and likes to let everyone know about his opinions, whether asked or not.

Published – April 17, 2025 03:28 pm IST