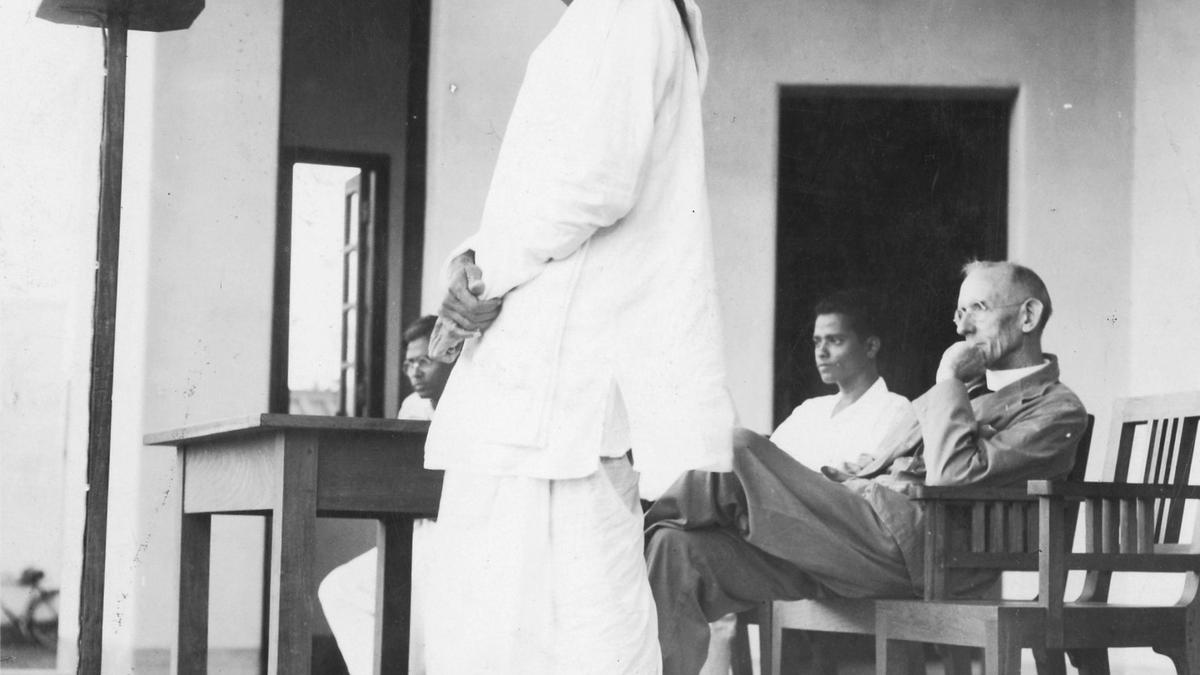

Change in stance: In this undated photograph, C. Rajagopalachari addressing students of Madras Christian College on the importance of the mother tongue and the place of Hindi as a common language of India. Principal Rev. Dr. Alfred George Hogg presided over the meeting. Years later, he fought against the imposition of Hindi on India.

| Photo Credit: THE HINDU ARCHIVES

In 1937, C. Rajagopalachari (Rajaji), as the head of the Madras Government, proposed to introduce mandatory learning of Hindustani in Classes VI to VIII. His move led to the Justice Party launching the first anti-Hindi agitation in the country. Rajaji defended the decision, saying the Hindustani language was like a “chutney on the leaf” and it was up to individuals to “taste it or leave it alone”. In 1940, the British Government withdrew the order.

However, 30 years later, Rajaji emerged as one of the strongest voices and passionate advocates against attempts to impose Hindi on the country during the adoption of the Official Languages (Amendment) Act and the Official Language Resolution. Accusing the Hindi-speaking people of fighting for breaking up the country, he called for continuation of the agitation against Hindi imposition in the interest of national unity.

A landmark public meeting

“Even if everybody gives up this fight, I am not going to give up this battle,” Rajaji said amid cheers in an hour-long speech on December 22, 1967, at a public meeting held in Madras, according to a report published in The Hindu. “I have a few more years to live, thanks to your prayers. I have fought battles as a single man and I shall continue to fight with all my conviction on the language question too,” he declared.

The agitation, he said, would have to go on incessantly “until we get the Hindi-speaking people defeated on this issue”. In fact, he urged the people to strengthen the hands of the State government in its fight against the imposition of Hindi as Madras (Tamil Nadu) could not rely on the neighbouring States in this regard.

Rajaji likened the Official Languages Bill to the legendary Dead Sea apple which turned into ashes in the mouth. “If it is useful, it is a variation of the Constitution; then, it is invalid because it is not done through the process of amending the Constitution. If the Attorney-General is going to argue that it is not a variation of the Constitution, then there is nothing that we will get out of the Bill. It is therefore a deception,” he said.

The Congressman-turned-Swatantra Party leader strongly believed that Hindi could not conquer the Tamil people with the help of the majority of votes in Parliament and “a few disturbances here and there”. “It might have been possible in the olden days. To establish Hindi Raj, the Hindi-speaking people would have to go through the same process through which the British Government went. It was possible then, because the people were backward. Today we are not backward. We will not allow ‘A’ to rule over ‘B’. Therefore it is an impossible proposition that the Hindi-speaking people have put before us. It can never be accepted,” he said at the public meeting.

Writing about the issue in his publication Swarajya in early 1968, Rajaji, without mincing words, pointed out that Hindi was not the language of the majority of the Indian people. Even if it had been the dominant language, the majority would not have had any right to coerce the minority into acceptance of this kind. “Hindi is, at best, the language of a large minority, even as Tamil is the language of a medium-sized minority, and Tulu of a small minority of our people. Apart from this, Hindi cannot claim to be a fully grown and integrated language. Its many dialects prevent its being called a language in its own right. Even in its most advanced form, Hindi as a language is inadequately equipped with the technical terms required for conveying modern knowledge,” wrote the elderly statesman.

According to The Hindu archives, Rajaji felt that students in Madras were continuing their agitation against Hindi imposition in December 1967 even after a Minister had appealed to them to stop it, since they probably felt “the elders were not fighting it properly”.

He was of the view that the youngsters, who had been demonstrating, were those who would be most affected by the imposition of Hindi. Even though the college boys had accepted the Chief Minister’s (C .N. Annadurai’s) assurance, boys under 12 appeared to be dissatisfied with it, and they went about shouting, “Down with Hindi”. Though Rajaji wanted the students to give up violence and agitations, he made it clear that they should be firm in achieving their goal of retaining English as the official language. “We must fight to the end. We cannot accept any compromise,” he said.

Faulting Assembly resolution

When the Madras Assembly adopted a resolution rejecting the three-language policy and instead adopting the two-language policy (Tamil and English), Rajaji had a slightly different view on the use of official language.

A report of the news agency, United News of India (UNI), published in the January 30, 1968 edition of The Hindu, said he felt that the Madras government, in its resolution on the language adopted by the Assembly, should have demanded the continuance of English as the sole official language of the Indian Union and as the link language among the States. “I am unable to understand the demand put forward by the Madras Government that all 14 regional languages should be made all India official languages of the Union,” the UNI report quoted him as writing in the Swarajya. He has characterised the proposal as “impossible”. Rajaji added that the proposal seemed to be “more in the nature of an argument against discrimination than a demand”, the agency said.

Published – March 04, 2025 10:55 pm IST