Rollo Romig

| Photo Credit: Evia Photos

Rollo Romig, American journalist, essayist and critic, has been reporting on South India, mostly for The New York Times Magazine from 2013. He also writes for the New Yorker. His first book, I Am on the Hit List: Murder and Myth-making in South India, is an investigation into the life and death of slain editor-activist Gauri Lankesh, a prism through which he captures the rise of what he calls an “electoral autocracy” in India. Edited excerpts from an interview.

A candlelight vigil for Gauri Lankesh, soon after her murder in Bengaluru.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

In the Introduction, you say you wanted to write a book on South India. Why did you then choose to write about the life and death of Gauri Lankesh?

I have been writing about South India for over a decade now, covering the region from various angles. The story of Gauri Lankesh touched on what interests me about South India, its literary scene, language cultures, character of its cities and legacy of communal harmony which was Gauri’s signature cause as an activist. I really felt Gauri’s story illustrated for me so much of what I love about South India and what is presently under threat.

A file photo of Gauri Lankesh with her sister Kavita Lankesh.

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Investigation into who killed Gauri Lankesh also becomes an investigation into who she was in the book. As someone who did not meet Gauri in her life, what was your impression of her?

It is odd to write a book about someone whom you have never met. Trying to know her through her friends, I was struck by how people who knew her when she was young could never imagine what she became before she died — very political, passionate and outspoken. She had metamorphosed so much. Actually, her work as a journalist is not as important as her work in connecting people. The outpouring of grief following her death, showed how she connected with such diverse sets of people. Even those who turned up did not know how many more people she had connected with. Her talent to connect people really matured into movement building talent, the kind of talent that often goes underappreciated. People realise it’s important only when a person who has been doing it is gone.

Artists, filmmakers, actors, journalists and intellectuals protest the killings of journalist Gauri Lankesh and others such as M. M. Kalburgi, Dr. Narendra Dhabolkar and Comrade Pansare, in Mumbai.

| Photo Credit:

Arunangsu Roy Chowdhury

The book also dives into another investigation as to why Gauri Lankesh was killed. Tell us more about that.

There was a lot of speculation that slain scholar M. M. Kalburgi and her advocacy for the Lingayat cause may have led to them being killed. But investigations have now shown that the primary motive for both their murders are single quotes from single speeches. The killers seem to have decided that they can’t allow the person who said this to live. Maybe who Gauri Lankesh was and what she did also came into play. But both the statements of Gauri Lankesh and Kalburgi were taken out of context. They fell victim to the contemporary sound bite culture, where you seize on a single sentence and the viewers always give them the least positive explanation, a sign of extreme polarisation. This also shows how Hindutva has been making a concerted effort to narrow down what is acceptable as Hinduism, trying to introduce an element like blasphemy, completely absent in Hinduism which is essentially a vast constellation of cultures.

Gauri Lankesh in Bengaluru.

| Photo Credit:

K . Bhagya Prakash

Gauri Lankesh openly rejected neutrality, that traditional journalism swears by. As a journalist, how do you assess her journalistic work?

Gauri really made me think about this question of neutrality and she has influenced me a lot on this question. Her father P. Lankesh, an English professor and a modern Kannada fiction writer, was also a non-traditional journalist. Gauri then was a more traditional neutral journalist. But once she took over the paper after her father’s death, she became more and more non-traditional in another way and took it to activism. She rejected many traditional practices, like she did not fact check, never used allegedly, did not seek the version of the other side. In these aspects, I think I will stick to the traditional practices of journalism.

But I have come to see neutrality as a defensive false position, essentially favouring the status quo. I have an opinion and I won’t pretend that I don’t. Should I strive to listen to all viewpoints, yes. But I have realised that some ideas are dangerous and cruel and I am now less hesitant to say so any more.

You have included two interludes unrelated to Gauri Lankesh’s story in the book, but still interact with the way we perceive her story. Why did you write these two interludes?

These are two different stories in the neighbouring states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu, which I had been covering simultaneously. It was an instinctive decision to include these. In ways that I am not able to articulate it yet, having them has made the book more complete, I feel. However complicated your storytelling is, you can’t capture the sense of a place and time without telling multiple stories. The interludes are also a tribute to the Indian form of epic storytelling as a mesh of multiple stories.

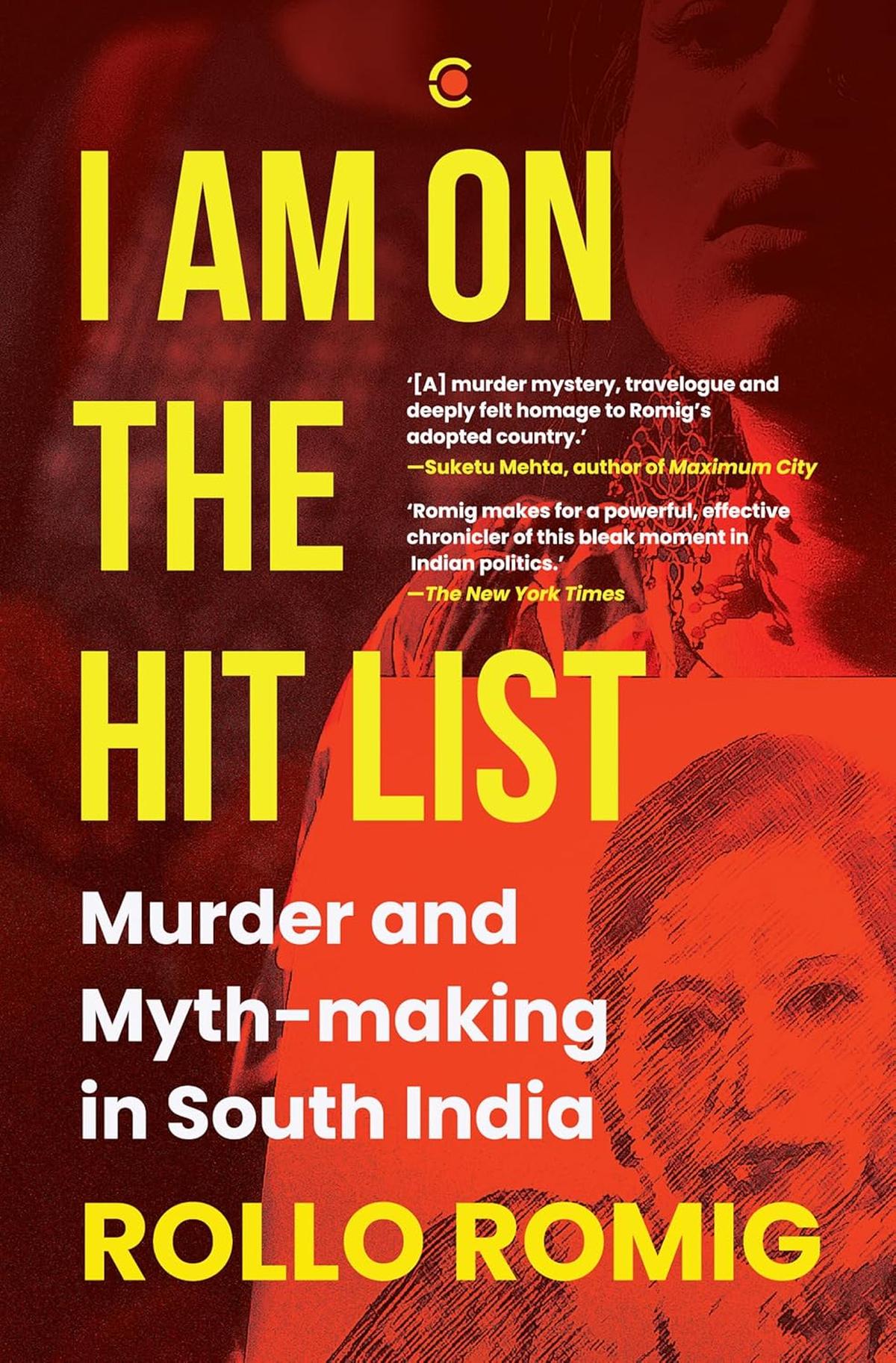

I Am on the Hit List; Rollo Romig, Context, ₹799.

Published – April 25, 2025 09:35 am IST