Often a lot of ignorance, and not a little distrust, marks the socio-political discourse between north and south India. Be it the history books which give expansive space to north Indian rulers, from the Mauryas and the Guptas to the Sultanate and the Mughals, or the latest delimitation exercise plans, the dice is loaded in favour of the north. Voices from the south have often attempted to correct the balance.

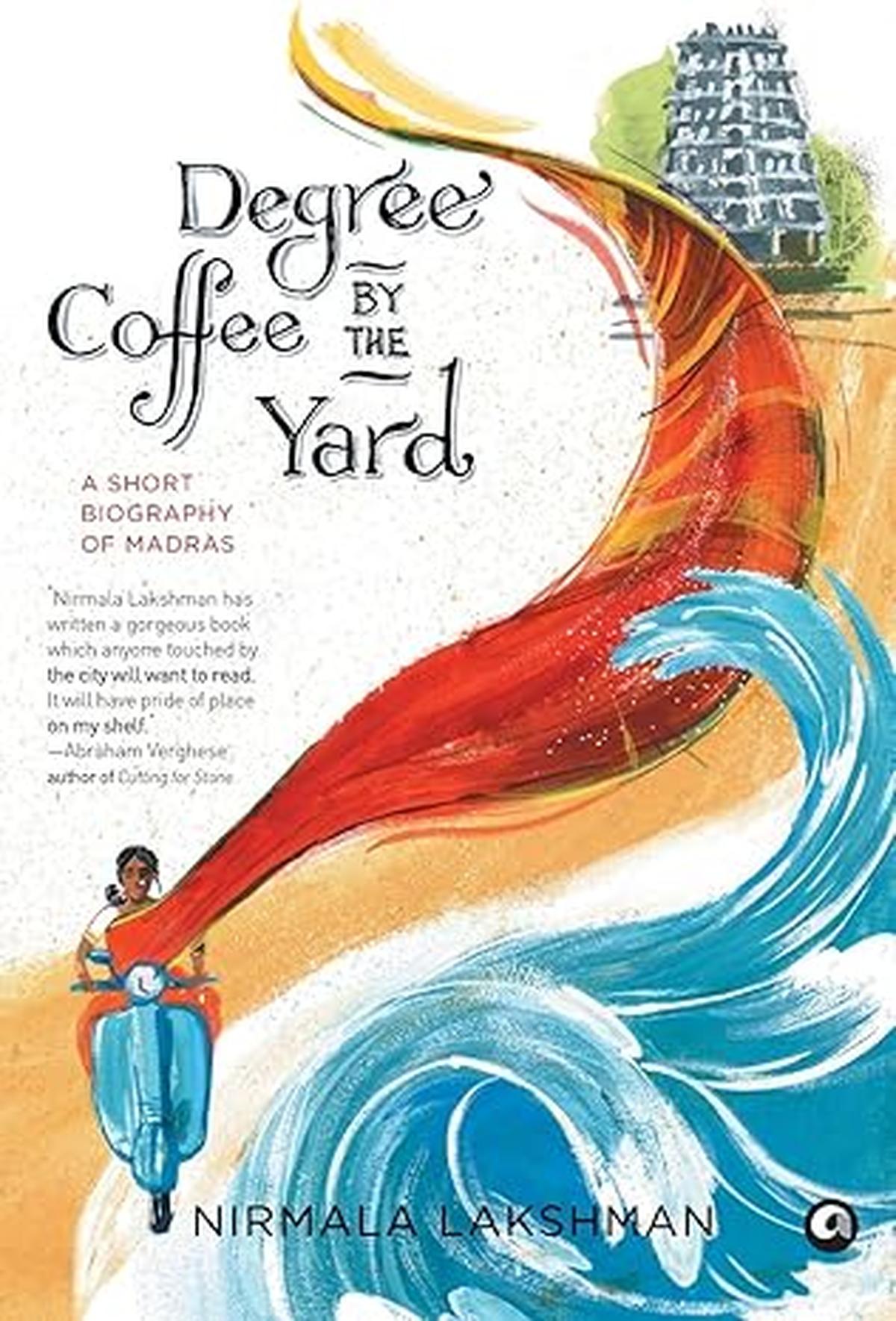

Nirmala Lakshman, for instance, has opened a window to the socio-political realities of the south, particularly Tamil Nadu, first with Degree Coffee by the Yard, and now with The Tamils: A Portrait of a Community.

The Tamils defies easy definition. Lakshman writes with enduring love about the geography of Tamilakam. “The ancient Tamils classified the topography of Tamilakam, their land, into five distinct categories. Each category was symbolised by a flower indigenous to that region: the kurinchi, a rare mountain bloom; mullai, the fragrant jasmine flourishing in the forests; the blue water lily of neytal, representative of the seashore; the desert flower of palai, emblematic of the arid lands; and marudam, also known as the queen’s flower, of the lowlands.”

Yet the book is not about geography or history alone for that matter. Yes, it is about the Pallavas, the Pandyas and the Cholas, but hers is not the work of a historian with a top-down approach. The focus is not so much on Rajaraja I or Rajendra Chola but little things that make a society a state. Like when she talks of Shilappadikaram and how Ilango Adigal calls Madurai an immortal city, she says, “The cities and towns of Tamil Nadu have their own histories and stories to tell. Chennai, once Madras, a sliver of sandy terrain cut out from a blue bay and bought by an impecunious English agent, Francis Day, trying to make his way into the world, is now India’s fourth largest city. Madurai, the city of temples, of jasmines, the seat of Sangam congregation, written up by Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to the Mauryan Empire, is as energetic and bustling as it was two millennia ago.”

Great cities and towns

Writing about Thanjavur, she says its where Rajaraja built a magnificent temple to Brihadeeswara, more than a thousand years ago, and it was “once the capital of the glorious Cholas where history’s shadows fall on stones, speaks to a culture of high art, music and dance.” Cities like Coimbatore “signal a proud industrial modernity.” In between are smaller towns, “scattered along the alluvial plains, in the Kaveri basin, the rice bowl of the Tamil country: Tiruchirapalli, Chidambaram, Kumbakonam.”

Between the Tamil country and cities and towns, Lakshman paints a portrait of a community, and its places. At a time when a debate over languages is raging — the imposition of Hindi and the antiquity of Tamil — Lakshman’s book nudges you to read. With good old journalistic tools of painstaking research, interviews, rigorous interrogation of claims of a glorious past, she presents things as they are.

Divisions and hierarchies

The rough edges of the past are not ignored. She writes of the differentiation in the Tamil Muslim community. “Social divisions are not caste hierarchies in the Tamil Muslim community. They are loose community-based structures and like in early Hindu society, based originally on professions. These divisions are flexible…Marriage between these groups is not uncommon.”

Lakshman writes about the origins of many Muslim groups. The Sha’afis follow the matrilocal system at places like Kilakkarai and Kayalpatnam, and the Marakkayars are descendants of Arab traders, and were originally boat and ship makers and ship owners. She talks about the Labbai who were of Arab descent too, but they came as helpers. “Apparently, these helpers would respond to the call of their masters with the term, ‘labbaik’, which translates roughly to ‘here I am’.” Incidentally, this is a term Muslims use when they go on the Hajj pilgrimage.

She clears the picture about the State’s role in India’s freedom struggle, and of Gandhi’s tremendous impact. “He came to the various towns and cities in Tamil Nadu at least twelve times, and seven of his visits were to Chennai.” It was in Madurai in 1921 that Gandhi resolved to abstain from a more formal way of dressing and adopt the loin cloth, that became “the image that defined him”. There was, of course, more to Tamil Nadu’s participation in the freedom struggle. For instance, V.O. Chidambaram Pillai’s struggle for Swadeshi and the famous March 13 protest in 1908 following which he was arrested, and treated not like a political prisoner, but an ordinary criminal, yoked to the oil press in place of a bull. Or the Vedaranyam Salt March of Rajaji which mirrored the Dandi March.

Social justice

Interestingly, while it’s popular to talk of social justice today, it was Tamil Nadu back in 1916 that saw the birth of the non-Brahmin movement spearheaded by T.M. Nair and P. Theagaraya Chetti. It led to the demand for proportional representation — something which politicians are demanding in 2025 through a caste survey. Periyar was to use this discontent and aspiration to usher in lasting change. Again, Lakshman opens a window to the past, letting the reader breathe in fresh air.

In many ways, The Tamils is Degree Coffee by the Yard on a bigger canvas. In that book, she talked about Chennai, writing, “Archaeological digs conducted by the British geologist Robert Bruce Foote in 1863 and 1864 in Chennai suburbs like Pallavaram and Attirampakkam revealed a hand axe (the first discovery of an Old Stone Age tool in the entire Indian subcontinent) followed by the discovery of a number of other tools of the same era, indicating the presence of people of the Stone Age. Iron Age implements found in Guindy, now very much in the heart of Chennai, also point to the antiquity of the region in which the city now stands.” With this vast sweep, taking in myriad strands of what it means to be a Tamil, Lakshman’s works are an eye-opener for those in the north who think, Chennai, and indeed, Tamil country, is only about idli-vada-sambar.

Published – April 10, 2025 08:30 am IST