A decade has passed since the Devendra Fadnavis government promised to make Maharashtra ‘drought-free’ via its flagship scheme Jalyukt Shivar Abhiyan. Currently in his third term as CM, Mr. Fadnavis announced ‘Jalyukt Shivar 3.0’ to repair existing water conservation structures, expand satellite-based mapping of these structures, and enable live-monitoring via a website and a mobile application.

“There were a lot of benefits of Jalyukt Shivar Scheme in the State. After CM Eknath Shinde came to power, we started Jalyukt Shivar 2.0, this second edition is ending now. We are starting phase three of the scheme soon in which repair of the current water conservation structures and new dimensions of water conservation will be done,” said Mr. Fadnavis to reporters, shortly after the launch.

Launched statewide, the Jalyukt Shivar scheme is based on the successful implementation of the village-scale scheme Jalyukt Gaon Abhiyan where five districts in Pune were made water-sufficient by 2012-13. In coordination with State departments, the groundwater level was increased from one to three meters and decentralised water reservoirs measuring 8.4 thousand million cubic feet (TMC) were created.

As of date, 22,581 micro watershed works have been completed, costing the state exchequer ₹ 9,731 crore. However, the situation remains stark as atleast 73% of the state was under drought-like conditions in May last year, with dam levels dropping as low as 10% in Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar.

Also Read: MVA govt. discontinues Fadnavis’s pet project Jalyukt Shivar Abhiyan

Here’s a look at Jalyukt Shivar’s aim, implementation, pitfalls and politics.

Objectives, partners and supporting schemes

Targetting 25,000 villages in a span of five years, Jalyukt Shivar was launched by newly-elected CM Devendra Fadnavis in December 2014, to make Maharashtra ‘drought-free’ by 2019. The first phase of the scheme focused on increasing the groundwater level, limiting run-off rainwater within village boundaries, expanding irrigated areas in the State and providing drinking water supply to all.

For water storage, it aimed to build decentralised water reservoirs, restore defunct water storage structures like dams, ponds, cement tanks, and percolation ponds. Engaging the public in its mission, the scheme also focused on desilting existing water tanks, tree plantations, increasing public awareness and promoting rainwater harvesting.

The State’s soil and water conservation department spearheaded the scheme, partnering with non-governmental organisations (NGOs), private companies and citizen groups. Drawing funds from the departments’ various schemes, District Planning and Development Councils, MLA and MP Local Area Development and corporate social responsibility (CSR) contributions, the scheme has created 39 lakh hectares of irrigated land and 27 lakh TMC in water storage.

Supplementing JSA, the State government has rolled out several other schemes through the years. Farm Pond on Demand (Magel Tyala Shet Tale) offers a subsidy up to ₹75,000 to farmers to construct ponds to minimise crop losses and soil moisture deficiency. Other schemes are Galmukt Dharan-Galyukt Shivar which removes silt from dams and spreads it across fields for soil fertilisation, Krishna-Marathwada Lift Irrigation Scheme to draw water from Krishna river basin to Osmanabad (now known as Dharashiv) and Beed; the Chief Minister rural drinking water scheme; Samruddha Maharashtra Janakalyan Yojana and Chief Minister Water Conservation Scheme, which takes up repairs to existing water sources.

The State’s agriculture department also introduced the Nanaji Deshmukh Krishi Sanjeevani scheme which uses climate-resilient strategy in farming as a long-term, sustainable measure. It incentivises water conservation measures, climate resilient seed production and protected cultivation techniques, while increasing participation of women farmers.

In collaboration with the Centre, the State is supplementing JSA with the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchai Yojana (PMKSY)— an amalgamation of ongoing schemes to implement irrigation at the field level, expand cultivable area, reduce water wastage, recharge aquifers and use precision-irrigation; and the Baliraja Jalsanjeevani Yojana which plans for irrigation projects in suicide-prone Vidarbha and drought-prone Marathwada.

JSA’s most ambitious partner is the State’s Marathwada Water Grid. Pegged at ₹ 40,000 crores, it aims to link major dams across area such as Jayakwadi, Majalgaon, Lower Dudhna, Yeldari, Vishnupuri, Manjara, Mannar and Sidhdheshwar to overcome drought. While these projects have been discussed in cabinet meetings through the years, the State is seeking financial aid from the Centre and World Bank for its implementation.

Explaining the pitfalls of this mega plan, Shripad Dharmadhikary, founder of water research organisation Manthan, says, “Marathwada grid project is a mini-version of the interlinking of rivers project…. People will fight against it when you say you are diverting their waters to somewhere else. Already due to dams, there is an impact downstream and rivers are drying up. If you extract even more water from here, it could exacerbate the downstream problems and other ecological problems.”

He adds, “Ecologically, when you mix water of one basin into another, invasive species of fish, flora and fauna will come with the water, which can harm or destroy the local species.“

Implementation and budgetary allocation

2015-2019

In its first budget, presented in March 2015, the Fadnavis government allocated ₹1000 crores for JSA, ₹500 crores for Cement Nala Bandh Programme for constructing water tanks, ₹100 crores for repair and renovation of water reservoirs in Gadchiroli, Bhandara, Gondia and Chandrapur and ₹1000 crores for a decentralized water management system. Throughout the year, 6,205 villages from 34 districts were selected and 2,53,862 works of water conservation were completed. Total expenditure incurred for JSA alone was ₹3831 crore, including ₹1847 crore spent from special funds and ₹389 crore via public participation.

Despite these works, as per Groundwater Surveys and Development Agency (GSDA), by April 2016, more than 10,500 villages which had received lesser than 20% of the expected rainfall i.e >20% rainfall deficit, had seen more than one metre drop in ground water levels, pushing them further towards drinking water scarcity.

Through five years of the scheme, a pattern was noticed where the initial budgetary allocation remained more or less the same at ₹1000 crore, but expenditure and public participation dropped drastically.

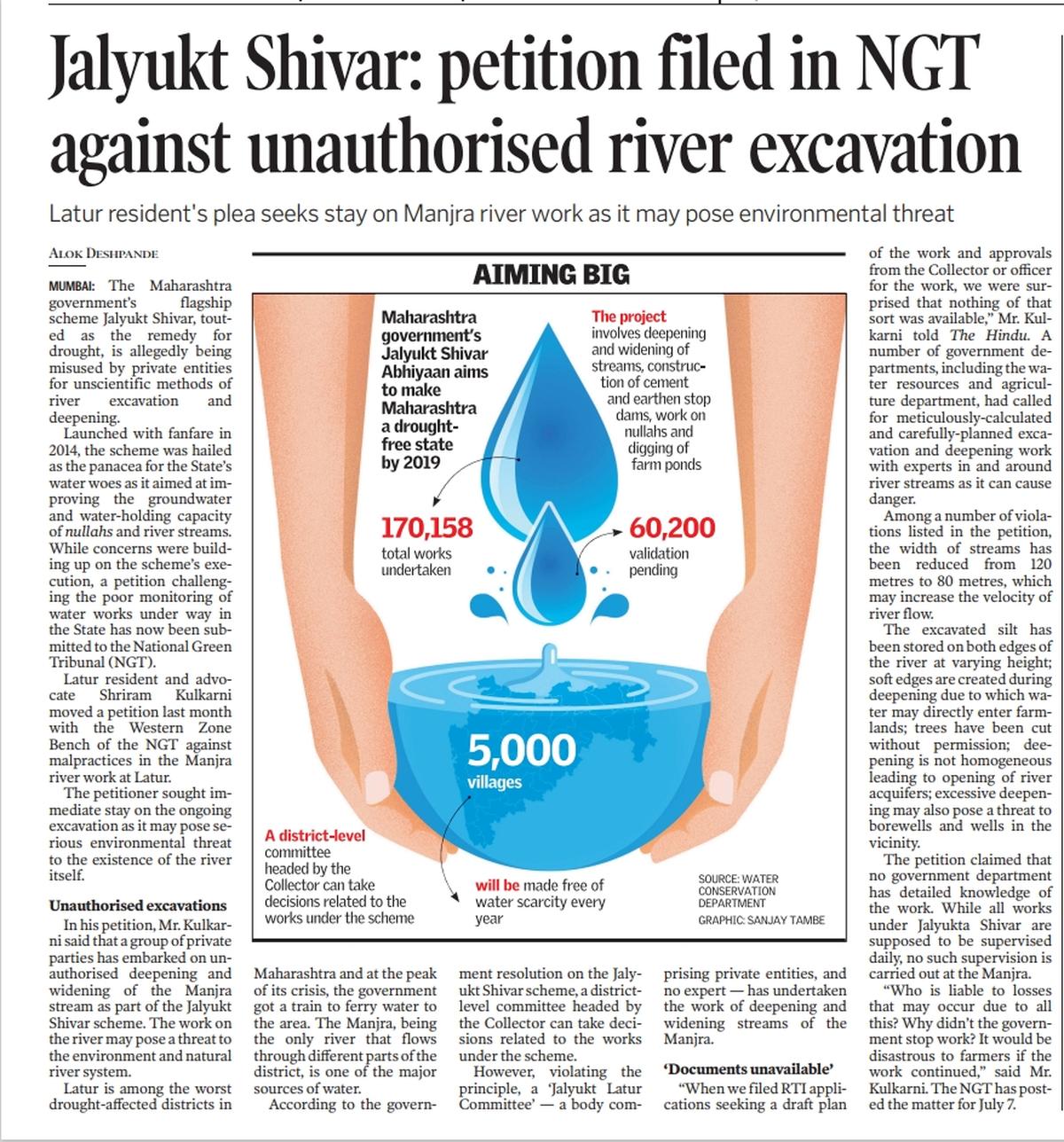

The shortcomings in JSA’s implementation were highlighted through a plea filed by Latur resident Shriram Kulkarni with the National Green Tribunal (NGT) in May 2016. Speaking to The Hindu, Mr. Kulkarni detailed how a Jalyukt Latur Committee comprising private entities and no geological expert was deepening and widening the streams of Manjra river – the sole river flowing across Latur. As per government rules, only a district-level committee headed by a Collector was empowered to decide on works related to the scheme.

The unauthorised deepening had reduced the river’s width thereby increasing its velocity, trees were felled without permission, excavated silt was stored on river banks endangering flooding of farm-lands and excessive deepening was threatening the borewells in the vicinity.

There were further challenges with the farm pond scheme, where individuals would dig pond on their farm to store rainwater.

“These ponds (with lining) are large and avoid seepage so they cannot perform groundwater recharge. What happened was that farmers filled the ponds by pumping ground water itself whenever electricity was there. This had some benefits for farmers but for larger hydrology it had none,” says Mr. Dharmadhikary.

Sachin Tiwale, a Fellow at Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and Environment, specialising in Water and Society programs, explains: “Farmers do this because by February/March, the wells dry up and they won’t get any water till monsoons. So by September, he fills the farm pond and uses it through the summer. This is privatization of a common property resource, i.e. groundwater, which is ideally owned by all. But farmers compete by the end of the monsoon and start taking whatever water they can from the aquifer itself. This is mainly found in horticulture belt where these farms ponds are 0.5-1 acre in size and go 20-30 feet deep. This acts as a storage structure and has accelerated exploitation of groundwater.”

Another field study by the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP) in 2017, deemed the scheme unsustainable. Speaking to The Hindu, researchers explained how indiscriminate digging of farm ponds had accelerated the rate of groundwater extraction. Stating that the unscientific implementation and undue reliance on machinery had resulted in provided farm ponds at the cost of depleting groundwater reserves and soil infertilisation, an officer from Sangamner told The Hindu, “Once the farmer constructs the pond, it is impossible for us to tell him not to use it for groundwater storage.”

The repeated claims of corruption in JSA’s implementation by activists, locals and even BJP’s ally Shiv Sena, forced Mr. Fadnavis to order an inquiry into the irrigation department and the public works department on May 17, 2017. Sena had highlighted how work done under the scheme in Dapoli, Khed and Mandangad was only on paper and that bills upto ₹10 crore were cleared for non-existent works. Four officials were suspended after the panel found irregularities in the allocation of funds.

Rainfall received across Maharashtra was erratic between 2015 and 2018. However, since then, the State has received normal rainfall. Despite the JSA works done in 2015-19, the number of talukas/villages in Marathwada and Vidarbha which faced drinking water scarcity remained high. In 2019, despite normal rainfall, these two regions recorded similar levels of scarcity. Since the scheme ended in 2019, rainfall has been normal and the number of villages facing water scarcity has also dropped, showing JSA’s ineffectiveness in tackling drought issues. The graph below traces Maharashtra’s water scarcity between 2015 and 2022.

There were individual success stories highlighted by the State department in the face of the Opposition’s accusations of shoddy implementation.

A case study of JSA’s implementation in Padali Helgaon village in Satara district during 2016-17, found a 11.69% increase in ground water levels, and water run-off was reduced via contour bunding increasing soil moisture retention to 92%. Kharif and Rabi crop production too increased to 340 kg per hectare and 387.5 kg per hectare respectively and fodder and poultry production also saw a hike. The research also extolled the employment generated for locals under JSA’s work guidelines and the improved social and economic condition of residents.

In contrast, a Businessline report pointed out that 26 of Maharashtra’s 36 districts (72%) were facing drought and crop failure in June 2019. Over 7000 water tankers were plied by the State government and an equal number of private tankers were running across Maharashtra. The government had allegedly allocated the work of free water supply to tanker owners who are affiliated with political parties, leaving locals to mercy of the tanker mafia. The State government itself admitted to irregularities in 1300 JSA works, ordering a probe by the anti-corruption bureau.

CAG report and stalling

As power changed hands from Mr. Fadnavis to Uddhav Thackeray, the scheme was not renewed in the 2020-21 budget after it expired in December 31, 2019. Stating that the BJP-Shiv Sena government had already spent ₹9707 crores for 6,32,708 works in the past five years, the State’s Water Conservation Minister Shankarrao Gadakh stated that deadline for incomplete works would be extended till March 31 after which the scheme would be reviewed.

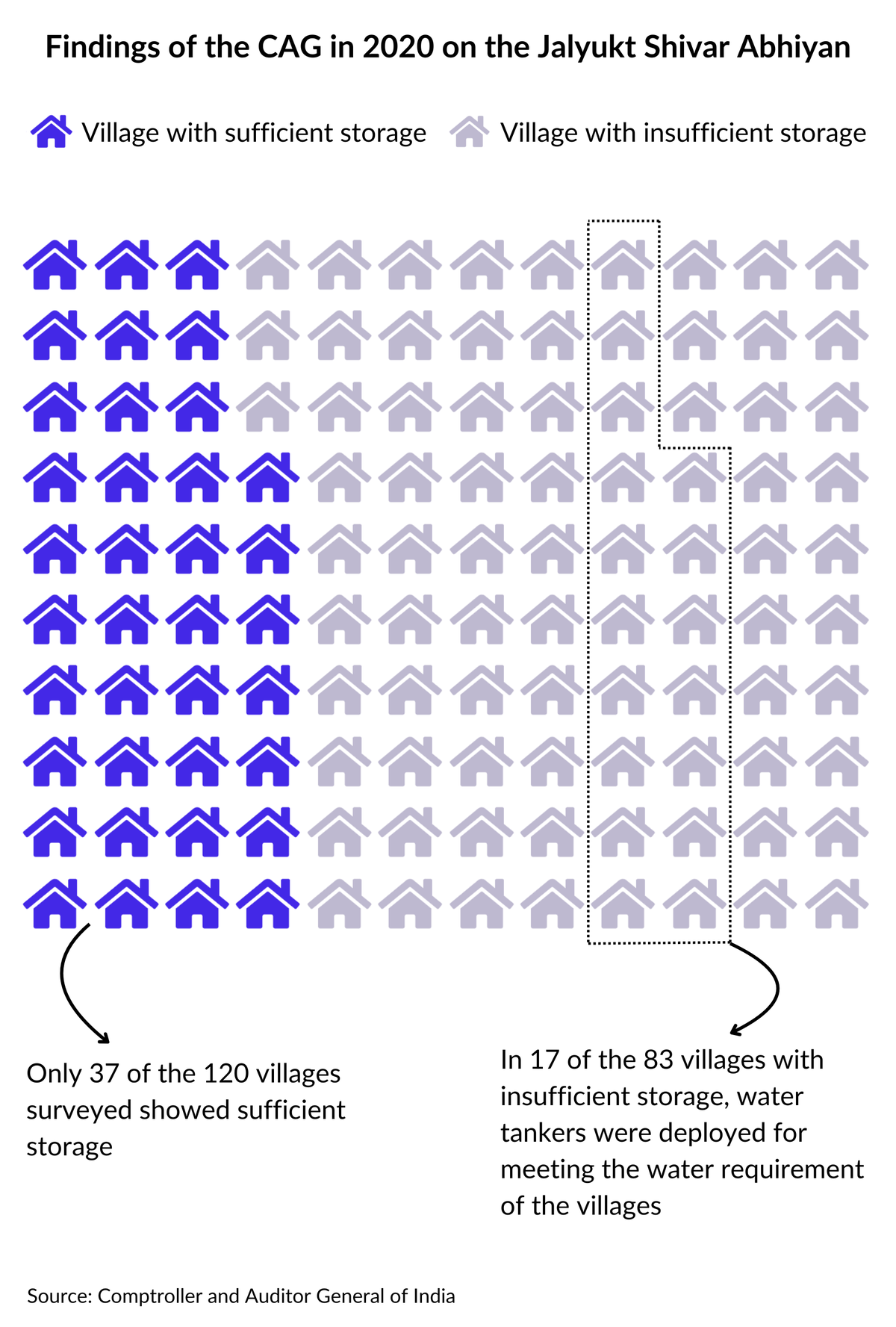

The biggest setback for Mr. Fadnavis’ government was when the Comptroller and Auditor General of India’s (CAG) report on JSA was tabled in the Maharashtra Assembly on September 8, 2020. The report stated “despite spending ₹9633.75 crore, the Abhiyan (mission) had little impact in achieving water neutrality and increasing ground water level.” Auditing the works taken up between January and December 2019, the report found that in 83 of the 120 villages selected for the study, the storage created was not sufficient to meet the water requirement. In 37 of the 83 villages, the shortage was due to less storage created than planned; the shortfall often more than 20%. Highlighting irregular monitoring of progress by district authorities, the CAG also pointed out that an additional expenditure of ₹2617.38 crore had been incurred in six districts due to non-collection of cess for maintenance and repairs.

The CAG found that out of 58 villages, in 35 villages (58%), the groundwater level after implementing JSA had decreased while in one village there was no change in the groundwater level. In four of the 22 villages where an increase was observed in the groundwater level, there was a gain of between four to 15% only, despite increased rainfall. “Thus, the Abhiyan was not successful in preventing the decline in groundwater level in large number of villages thereby defeating the objective to increase,” it concluded.

Other observations by the CAG included the fact only 29 of the 80 villages declared as water neutral had actually achieved it; 38 of the 58 villages surveyed had witnessed no groundwater increase; only 21% villages had undergone third party evaluation and even those audits had questioned the structural soundness of the projects, and despite recommendations, there was an increase in the digging of dugwells and borewells.

Between 2021 and 2023, no additional JSA works were undertaken, as enumerated by the Economic Survey. A special investigation team (SIT) was instituted by the MVA government to probe into the scheme’s implementation.

Why did JSA fail and what are the alternatives?

“Whenever we do any soil and water conservation work, it should be a systematic plan, you start from the top of the watershed and go down the valley. You first do interventions in the upstream line, then the circuit area and then the drainage line. This is done to arrest soil and water which is coming from the high elevation towards the lower elevation within a village,” Mr. Tiwale says.

He adds, “In 1994, the Hanumant Rao committee said that these programmes need to be 3-5 years long, should have extensive engagement with the community and NGOs with mass mobilisation. Hence, we revised our guidelines and began implementing the Integrated Watershed Management Programme (IWMP). But in the past 15 years, Maharashtra is focused on technocratic and quick fix solutions.”

JSA was meant to make 5000 villages drought-free in a year, including water-budgeting and implementation. This was not possible, he asserts .

“To prepare a water-budget of a village, which should use a micro-watershed as a unit, requires six months to a year. Also the process requires tools to measure rainfall, water coming in and going out of the village, water requirement, water level and how it varies with tide and water extraction and if the village shares an aquifer with neighbouring areas. JSA says that the gram sabha should make the plan but does not provide any institutional arrangement for it and enough time, ,” he adds.

Offering an alternative, Mr. Dharmadhikary says, “What Maharashtra should be doing is looking at demand-side solutions. Maharashtra should move away from water-intensive crops like sugarcane. Also water distribution should be equitable. Maharashtra has the highest number of dams in the country, especially in drought-prone areas. The irony is that the second-biggest dam (after Koyna) is in Marathwada- Jayakwadi, but water distribution is not equitable. It is suggested that for every farming family which has cultivated land, atleast least one acre of their land should get irrigation – naturally via canals and gravity or artificially by pumping water.”

What is the State government doing now?

Power once again changed hands as Eknath Shinde split the Shiv Sena into two and walked away with 14 MPs and 41 MLAs to ally with the BJP in 2022.

The newly formed BJP-Shiv Sena government promised to launch Jalyukt Shivar 2.0 in March 2023 and the same was announced by then-Finance Minister Mr. Fadnavis in his budget speech. The second phase followed the same pattern, selecting 5000 villages to make ‘drought-free’. However, no additional expenditure was incurred as of March 2024. The total expenditure stood at ₹9731 crore and the completed works totalled to 20,544 – the same as June 2020. In the following year, ₹650 crore was allotted to JSA 2.0. During 2023-24 in all 49,511 works were completed and expenditure of ₹ 947.54 crore was incurred.

Officials in the Soil and Conservation department shared that the State government is currently implementing Jalyukt Shivar 2.0 in those villages which have not achieved water neutrality in phase-1 of the scheme. Moreover, villages which had not been selected for works will also be covered under this phase. As announced by Mr. Fadnavis, phase-3 of the scheme is in the offing. “Within the next three months, before the monsoon starts, we will be visiting all soil and water conservation structures built across Maharashtra in the past 20-25 years and verifying those and uploading it in the web portal. This will provide the necessary database for policy-making in the future,” said an official. Jalyukt Shivar 3.0 is slated to be launched within the next five years.

Published – March 07, 2025 08:43 pm IST