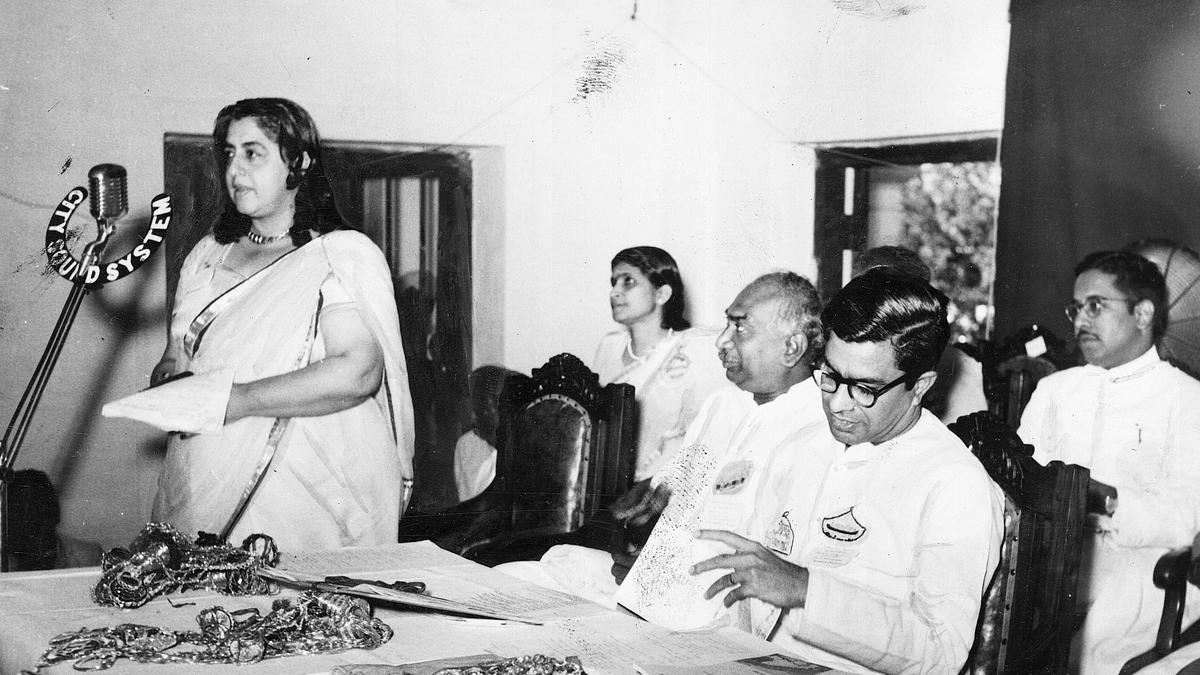

Along the bustling stretch of Casa Major Road, opposite the Government Museum at Egmore, Chennai, stand the Guild of Service (Central) and the Madras School of Social Work (MSSW) that are highly regarded for their social service. Though they are independent of each other, the name of Mary Clubwala Jadhav links them by a common thread. Historical records show Mary, who hailed from an affluent Parsi family, was associated with many social organisations, including correctional services, juvenile care, and women’s welfare. At least 150 of them were in Madras alone. She also founded the MSSW.

Born in Udhagamandalam (then Ootacamund) on June 10, 1908, Meher, as she was initially called, was a descendant of a Parsi family. Despite her privileged upbringing, she plunged into social work in school, showing interest in Girl Guides and Red Cross. An 18-year old Meher arrived in Madras after marrying Nogi Clubwala, the heir of entrepreneur Phiroj M. Clubwala, in 1926. After losing her husband at 27, Meher joined the Guild, according to the Guild of Service (Central) Seva Samajam, Spreading Hope and Happiness, a coffee table book by Rukmini Amirapu.

‘A living entity’

“When we talk about the Guild, most people ask us whether this is the place that Mary Clubwala Jadhav worked for, and we happily say, ‘yes’. The Guild before her was a very different organisation. Her presence, however, made it a living entity. I have been here for 25 years. Every day, when I walk in, I look at her portrait and think ‘let me do at least a fraction of what she did’,” says Himani Datar, honorary secretary of the Guild (Central).

The Guild (Central) came to be in 1923, through the efforts of a group of British women who came together in the early 1900s. Mary’s foray into the Guild in 1936, perhaps, marked the first instance of Indian women having been inducted into the institution. One of her notable contributions, as outlined in the book, was during the Second World War (1939-45). Mary and her team of women threw themselves into humanitarian efforts to alleviate the sufferings that the armed forces went through.

In 1942, Mary founded the Indian Hospitality Committee, with the support of the Guild, to offer services to hospitals and entertainment to the troops. Between 1942 and 1945, over 30 lakh soldiers, sailors, and airmen were entertained by the committee members. These efforts also earned her the moniker, ‘Darling of the Army’.

“One of the notable points of Mary was her dynamism and capacity to empathise. Not only did she think ahead of her time, she also had boundless energy and a drive to keep going. She saw things ahead of her time and the need to help the intellectually challenged, train school dropouts, and provide education to girls,” Ms. Datar adds.

A short biography, presented to Mary by the Social Welfare Organisations of Madras in 1956, briefs the institutions that she was part of. Besides playing a pivotal role in inducting men into the Guild, she founded the Madras State Branch of the Indian Conference of Social Work in 1948; helped to establish Seva Samajam Boys and Girls Home at Adyar in the 1950s; and ensured that social welfare institutions, affiliated to the Guild, received aid and gifts from international bodies like the UNICEF.

Reports from The Hindu archives reveal that she had been part of several independent organisations such as the Indian Colonial Society, the Central Social Welfare Board, and the City Leprosy Relief Council, and helped to fund maternity centres.

Her most renowned institution, the MSSW, “started against great odds. She had been making repeated, but futile, attempts since 1947 to start a social work school for students from the States of Madras, Andhra, Kerala, and Mysore. In 1948, when the Guild organised its first Conference of Social Work, a resolution was adopted to start an institute in Madras for men and women and provide a two-year course in social work. In 1951, Mary went to the U.S. and visited 20 Schools of Social Work and she was offered technical assistance and books…,” Ms. Rukmini writes.

The MSSW was inaugurated by Chief Minister C. Rajagopalachari in 1952. “Mary found that to continuously work in the sphere of social work, she needed professionals. That is why she visited various countries and started the MSSW on the lines of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences. We are continuing the legacy by upholding the standards of professional training in social work,” says S. Raja Samuel, principal, MSSW. Now, the college has forayed into policy space, advising the government on interventions for the elderly, women, and children, he adds.

Several firsts

One noteworthy characteristic of Mary, Mr. Raja says, was her deep-rooted connections within the government, which sometimes extended abroad. Ms. Rukmini’s book outlines how in 1956, the Home Ministry appointed her as one of the 12 correspondents in India in the field of correctional crime. She was the first woman Sheriff of Madras (1956); the first International Commissioner of Guides for India; and the first Indian lady volunteer to be invited to the U.S. under the Leader Specialists Program.

She also served as Vice-Chairman of the Madras State Social Welfare Board, and was one of the chairpersons of four panels formed to tour India and recommend social welfare initiatives to the government. Mary was also a nominated member of the Madras Legislative Council, and recipient of the Padma Shri, Padma Bhushan, and Padma Vibhushan.

Mary remarried in 1953 but towards the final chapter of her life lost her second husband Major Chandrakanth K. Jadhav and her son, Phil Khushro (from her first marriage).

“Even as she faced enormous personal tragedies, she never allowed them to come in the way of her social work. Any other person would have broken down. But she was a very different kind of woman,” says historian V. Sriram. He rejects the commonly held notion that the tragedies drove her towards social work. “It is wrong to assume that as she was doing a lot of work prior to that,” he says.

Mary died of cancer in Bombay on February 6, 1975. Though records of her illustrious life are available, they are scattered. And this hinders accessibility to her body of work. Her grand-nephew Maneck Dastur says, “Even today, we do not have an exact count of the organisations that she was part of or what she did. Today, with initiatives like Corporate Social Responsibility, it is far easier to engage in social work. So, what she did decades ago was commendable. Sadly, we do not recognise people like her, and we do not have enough records.” He calls for proper documentation of her life.

Published – April 24, 2025 10:25 pm IST