In 16th century Mughal India, four unlikely scouts set out on an imperial hunt through the length and breadth of the land, on the Great Moghul’s orders. What they uncover, about their mission and indeed, each other, forms the crux of Shandana Minhas’ new novel, Ferdowsnama (published by Penguin). Blending a tale of adventure with nuggets of history and wildlife, the Pakistani author, now based in London, paints a vivid picture of what it means to be a woman in medieval India. Edited excerpts from an interview:

Q: What inspired you to set this new book in medieval India when all your previous novels were set in contemporary times?

A: I moved to a country where some people were more interested in where I came from than who I was. That got me thinking about it, too. Where are you really from? The nation state is a blink in time so I did an ancestry DNA test. Apart from the expected Punjab, the map of my body included Sindh, Kashmir, Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. I started reading ancient texts and books about regional history. I began looking at art. And it gripped me.

Q. With ‘Ferdowsnama’ and its themes of class oppression and feminism, is your intention to hold a mirror to society?

A: I try to meet the page without intention, but I can’t control what travels unseen. Yes, Ferdowsnama is fantastical rather than realist, but my thematic preoccupation remains life in an unequal world. The fantastical offers both writer and reader the chance to turn away from superficial reality and enter a space where you can see things in a way it might be unbearable to allow yourself to do outside a book. In ‘real’ life, it hurts to know someone is looking at you and thinking you are less worthy. In the imaginative realm, you can hold that knowledge without it burning you.

Q. How did you go about the world-building of this novel? What did your research involve?

A: Some of the texts I read before writing Ferdowsnama were, of course, the Baburnama and Abul Fazl’s official records of Akbar’s reign. I also read translations of Somadeva’s Kathasaritsagara, the Devi Mahatmya, Ibn Battuta, and assorted collections and retellings of folklore, qissas, dastaans, etc. I should clarify that in the early stages I wasn’t reading these as research, I was reading for pleasure, out of curiosity, one text leading to another.

My world-building was also informed by what I was watching, which included the Netflix shows The Witcher and Tiger King. The ligers in Tiger King inspired one of the chapters. And a news story about the decimation of pangolin populations, so their scales can be used in traditional medicines, inspired another one. Animal welfare has also been a lifelong preoccupation. I can be a dispassionate observer of human nature, but I’ve never managed to tune out non-human suffering.

Underpinning all of these were my quickening memories of the land I’d left. The Thar desert in Sindh, where I spent two weeks shooting a film, and Sehwan Sharif, where I went for the annual urs… the imposing, otherworldly mountains and valleys in Pakistan’s northern areas, and the lunar beauty of Balochistan’s coastline and national park, through which I travelled for work and leisure. Vistas glimpsed through vehicle windows on long journeys — when I was a child, we also lived in Hyderabad [in Pakistan], and on holidays we would drive to Lahore. Every immigrant walks through their past while they walk towards their future.

Q. How did the character of Ferdows, the novel’s heroine, come about?

A: I was in the British Library reading imperial memoirs. There were so many silences and spaces in the texts, where women’s voices should have been. I wished I could hear one. Then I read the opening of the surviving text of Gulbadan Begum’s Humayunnama: “In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate! There has been an order issued. Write down whatever you know of the doings of Firdaus-makani and Jannat-ashyani…” — and suddenly I could. I could hear Ferdows.

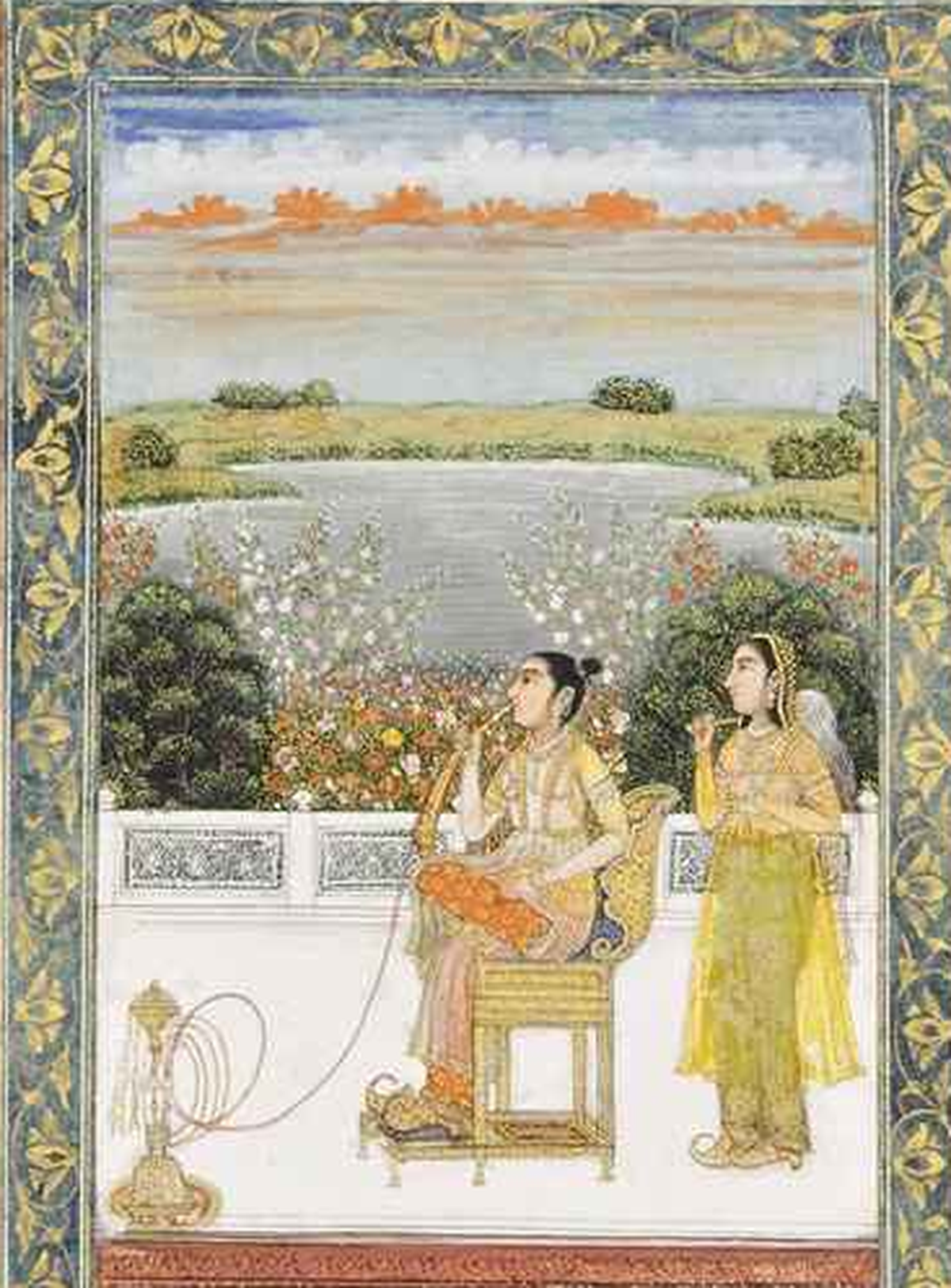

A 19th century portrait of Gulbadan Begum (seated), daughter of Emperor Babur, and author of the ‘Humayunnama’.

| Photo Credit:

Creative Commons

The pomp and splendour of the early Mughal era and other dynastic periods can be intoxicating. While I understand the lure of an aesthetically flattering light cast on our own pasts, how many women have been edited out of historical records, or made the supporting cast in their own stories? Babur’s daughter Gulbadan Begum, for example, led an interesting life herself. Why does only a part of the account she wrote survive? Where are the stories of the women on Ranjit Singh’s pyre? What was the woman on my Royal Collection tote bag doing when she was not gazing into the distance, in profile, holding a flower?

Q. ‘Ferdowsnama’ comes nearly a decade after your last work, ‘Daddy’s Boy’ (2016). Do you think you have changed as a writer? Have your compulsions or priorities changed?

A: I wonder if writers can change. I wonder if it isn’t their inability to change that drives them to constantly reshape, remake, reimagine the world around them instead. But I do think writers can grow. My compulsions and priorities remain what they’ve always been. Storytelling. Developing my craft. Whether I’ve managed that in the years since Daddy’s Boy is not for me to judge.

Q. Market figures say non-fiction is more popular than literary fiction in India. What about in Pakistan?

A: I’m not well placed to answer this because I don’t live in Pakistan any more but, anecdotally, non-fiction is more popular there too.

Q. You are a novelist who has also dabbled in publishing and theatre. Which do you enjoy the most? And does one feed into the other?

Dabbled is the right word. I’ve dabbled in many things over the years. Most recently, podcasting. Gigs, reading, conversations, memories, desires, travel, losses, gains, humiliations, everything I experience feeds my writing. You can’t make something out of nothing.

Q. Tell us a little about your journey with Mongrel Books, the indie press you founded and ran from 2016 to 2020. Would you like to revive it one day?

A: Mongrel Books, the small press my partner and I ran, only published three books but it got some attention, I think, because it said some things, about the dominance of entrenched interests in Pakistani publishing, that resonated. And because a microclimate for books outside the risk-averse mainstream is crucial to the growth of a healthy, living, culture.

I’m proud to have published the writers we published and made sparkling new friends [nobody really likes writers, everybody really likes publishers] but I currently have no plans to revive it. As long as Pakistan remains isolated from a wider literary ecosystem, it will remain a rigged market. Also, I no longer live there. Finally, Mongrel remains inextricably linked with memories of my father, my most ruthless adviser, and first and best fan [never read any of my books, bought all of them]. He died in the second COVID-19 wave.

Published – April 04, 2025 09:30 am IST