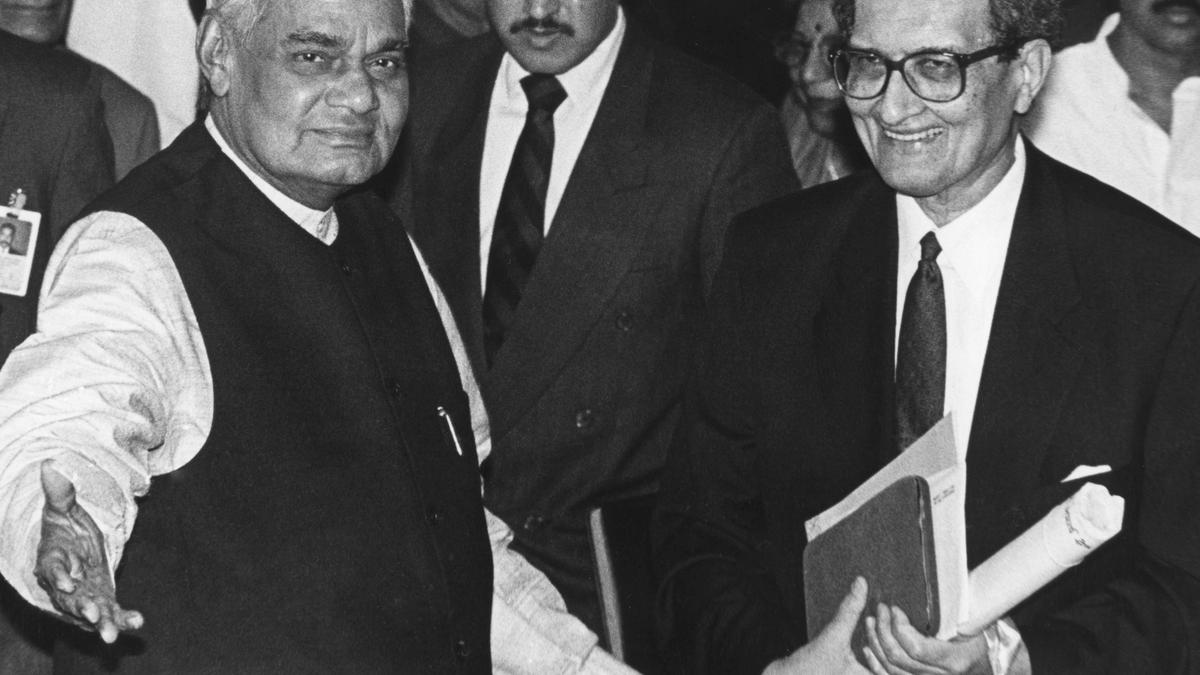

Prime Minister A.B. Vajpayee greeting Nobel Laureate, Prof. Amartya Sen, at the Durbar Hall of the Rashtrapati Bhavan in New Delhi on February 16, 1999.

| Photo Credit: THE HINDU ARCHIVES

Years ago, I asked the legendary teacher of economics, Professor Bhabatosh Datta, “Sir, What, according to you, is the focal point in the ‘economics’ thinking of your legendary student, Amartya Sen, who is not only revered as a superb social scientist but also as a profound philosopher ?” After pausing for a second, Professor Datta replied, “Economics to Amartya is like it was to Alfred Marshall — a handmaiden of ethics and a servant of practice”. When I reported this evaluation to the Nobel Laureate student, he replied, almost overwhelmed with emotion, “How can I ever repay my debt to that great teacher ?”

Bhabatoshbabu was unerring in his estimate. From his adolescence, Sen was wedded to ‘practice’. While he was a student of Patha Bhavan in Shantiniketan, he used to ride his bicycle and spend hours in the contiguous villages inhabited by Adivasis. He examined assiduously their quotidian lives, their struggle and deprivation. He handed over the bicycle to the Swedish Academy and it is now displayed in the Nobel Museum. Stressing the worth of this simplest vehicle, Sen wrote in his memoir Home in the World, “This bicycle had been with me since my schooldays. I had used the bike not only to collect data on wages and prices from inaccessible places, such as old farmsheds and warehouses, when studying the Bengal Famine of 1943, but also to transport the machine to weigh boys and girls up to the ages of five to neighbouring villages from Shantiniketan to examine gender discrimination and the gradual emergence of the relative deprivation of girls”. That was his praxis when he was only a schoolgoer.

A moral question

Is it then surprising that this ‘committed’ teenager would explore later as a researcher the intrinsic relationship between ethics or moral philosophy and economics? His entire worldview was nourished by the bond between the two, hence my first question to him on a cold, wintry night at Pratichi (the name of his house in Shantiniketan), was “Experts and laymen agree that you have gone beyond the accepted boundaries of your discipline, namely economics, and have penetrated into the realm of philosophy or ethics. Do you think this journey led to an epistemological break ?”

His answer was crystal-clear, “We need to recall that the subject of modern economics began in a very ambitious way with Adam Smith seeing economics as a part of a moral and practical philosophy. That seems to be the right perspective in which to see economics today… Indeed, many of the economic problems dealing with human welfare today, which, after all, is the basic motivation for all economics, clearly have philosophical dimensions that cannot be avoided. So, I wouldn’t consider it to be a radical epistemological break but an urgent return to the very foundations.”

The inexorable progress from this ethical stratum to the formulation of his leitmotif, namely the theory of Social or Moral Choice, was spontaneous. Deliberating on this crucial cogitation which fetched him the Nobel Prize in 1998, he stressed, “First, this subject enjoys a 200-year old tradition going back to the writings of Bentham, Borda and Condorcet. Second, in recent years, it has been immensely developed by Kenneth Arrow who gave it a systematic, mathematical format and posed some crucial problems which led to ‘impossible results.’ Third, I tried to deal with some of these ‘impossibilities’ and I proposed some solutions. Fourth, I found out that the format of Social Choice crossed the very narrow limits posed by utilitarianism and voting theories. Fifth, I must say that it played a major part in my understanding of the world”.

A critic of utilitarianism

His sharp critique of utilitarianism led to the next query: “If not John Stuart Mill, which economist or philosopher would you revere as the most eloquent exponent of our fundamental quest, our journey ‘from the realm of necessity to the realm of freedom’? His answer came like a cascade, “I affirm that Marx has discussed the issue most illuminatingly than any other economist. He was, of course, much more than an economist. In fact, in the Marxian valuation system, freedom in the positive sense, has a clear role which it does not quite have in any of the other standard moral philosophical system. I greatly value the redemptive and ethical vision of Marx.”

It is this indispensable principle of ethics and related practice that inspired Sen to discover appropriate correlatives in other disciplines. He told me more than once that he attached an inestimable worth to Immanuel Kant because his philosophy was embedded in ethical or ‘moral’ (that is Kant’s expression) engagement. His advice was, “Read Kant’s The Moral Law and his Critique of Pure Reason minutely. No other Western philosopher before him cemented ethics with reason in the way he has.”

Justice over rules

Similarly, he cherishes a pronounced love for the unforgettable Sanskrit play Mudrarakhasa by Sudraka because here the protagonist Charudatta and his consort, the dazzling Vasantasena, advocate the supremacy of nyaya or ethical justice while evaluating human conduct. In his words, “I interpreted Charudatta’s priority to be the pursuit of nyaya, seeking a good world in which we can live with fairness, rather than obey the niti of fixed rules.” (Memoirs, Page 101). No doubt this emphasis on ethics impels him to hit the nail on the head in our age of infinite conundrum and incessant conflict. Almost in the manner of infallible Euclid, he concludes, “All perceptible problems of the world originate from one form of inequality or another.” Sen, here is not indulging in any reductionism. Rather, he is positing the ineradicable essence of all human endeavour and aspiration.

His devotion to moral praxis helps us to scissor our countless cobwebs and we recall the consummate tribute paid by Nadine Gordimer, “Sen is one of the few great world intellectuals on whom we may rely to make sense out of our existential confusion.”

Subhoranjan Dasgupta, former Professor of Human Sciences, is an academic and writer based in Kolkata.

Published – February 20, 2025 08:30 am IST